“Everything was simpler back then. People wanted to be free. It’s different now.”

Despite my personal fondness for the 1999 original, I think it’s only prudent to question the need for a new Matrix film. There’s no doubt it makes sense from a marketing perspective. We’ve seen any number of much less culturally relevant franchises, ahem, resurrected and paraded back into theaters to tepid reception and outsized receipts. Any number of crusty elder statesmen forced to wriggle around as lithe characters they played in their youth. Any number of good things ruined by greed and a lack of imagination. And so what should we make of The Matrix Resurrections, a sequel/reboot of a franchise that hasn’t seen a new live action entry in almost two decades, whose creators had publicly stated that they did not wish to revisit the material, and which features meta-textual criticisms of the corporate arm-twisting that led to its creation within its very screenplay?

The Matrix Resurrections is the kind of film I want to either love or loathe. Give me a dismal attempt at a comeback that I can forget about as soon as I’ve seen it or give me another classic. Lana Wachowski, directing a film by herself for the first time, delivers a product that lands somewhere in the middle. Its most exciting wrinkles occur early, when we find Neo (Keanu Reeves) plugged back into the Matrix. But wait. How is Neo in the Matrix at all? Didn’t he and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) die at the end of The Matrix Revolutions? Well, yeah, they did. But as we will learn through a series of wishy-washy expositional conversations that strike the viewer as ridiculous but necessary to have these two in the story, they were brought back from death by The Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris), a program designed to study the human psyche. He discovered that their undying love for one another generated a mysterious energy that could overpower the whole system (as witnessed in the original trilogy). But, if they are kept in their goo pods in close proximity to one another, their mystical connection produces an increased energy output from all of the similarly plugged-in human batteries. It’s in this dire situation that the film begins.

Thomas Anderson (Reeves) has been convinced by his pushy therapist (Harris) that the events of the original Matrix trilogy were mental breakdowns instead of reality; that the glitches of code he sees are not rabbit holes to stick his nose into, but symptoms to be treated with prescriptive blue pills; that the soccer mom he sees at the coffee shop only coincidentally looks like the love of his imagined former life. In this new version of the Matrix, Anderson is a legendary game developer whose masterpiece was a famous trilogy—the first three Matrix games (obviously we take a little logical leap here to consider them as games instead of movies). The film shines its brightest when Anderson is approached about creating a fourth Matrix game. In a series of corporate focus group discussions, the script takes potshot after potshot at the modern cinema landscape, ripping into the coercive business practices of Warner Bros. (it suggests within the film that WB would have made it with or without Wachowski’s involvement), demographic analytics overtaking creativity, exploitation of nostalgia, media addiction, and so on. In this current era, most tentpole franchise films are distressingly cynical and seemingly incapable of earnestly approaching their source material. And so these films are laced with irony as they hold their subjects at arms’ length. This has, in turn, led audiences who previously appreciated these characters to also hold them at arms’ length. It’s truly sad. Resurrections ridicules this very phenomenon by having several members of Anderson’s team absurdly break down the “meaning” of the Matrix franchise and reduce it to loglines that wouldn’t inspire anyone (okay, they probably would, but that’s just proving the point). While I found this section to be the film’s high point, it’s debatable if it fits within the narrative structure of the Matrix universe.

In many respects, Resurrections as a whole can be seen as a sort of anti-sequel; a blistering critique of the solipsistic cinematic universes that dominate theaters and online discussion. It’s against these monolithic enterprises that Wachowski’s film stands nearly alone as the rare big-budget sequel that actually takes risks and makes a statement. The litmus test for its critiques comes in the form of a blockbuster rival, Spider-Man: No Way Home, another meta-textual sequel that was released the week prior to Resurrections. No Way Home sees the return of two previous Spider-Men (Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield) along with several villains from the older films. Even dismissing the fact that it stole its interdimensional premise from its animated cousin, it’s obvious that the movie is a carefully manufactured ouroboric monument that worships its own existence; a cynical celebration of the horrific feedback loop that has programmed mainstream audiences to defend its continued box office domination at all costs; a hollow, soulless shell of a movie that has made about ten times as much as Resurrections at the time of this writing.

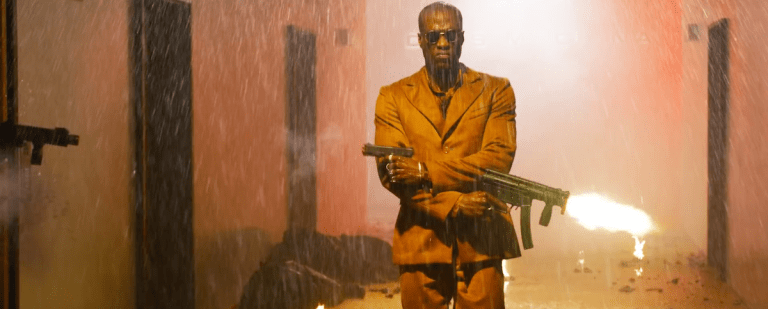

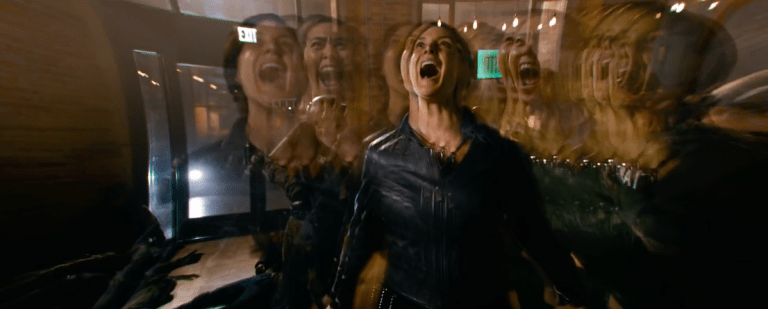

By contrast, Resurrections offers the red pill, also raising its old stars from the dead but with aims other than nostalgic comfort. Instead, it offers a startling sense of déjà vu that is then twisted into something new and exciting for those who haven’t approached it looking for cheap wish fulfillment. Even while it contains reenactments of iconic scenes, bountiful archival footage from the original trilogy, and the return of many characters, it offers these things in a subversive way, toying with expectations for its entire runtime while refusing to satisfy all but a few of them. “Morpheus” (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) returns as a bastard brainchild of Thomas Anderson, who wrote the program as a combination of Laurence Fishburne’s character and Hugo Weaving’s Agent Smith. Smith (Jonathan Groff) returns as well, acting as a temporary ally who doesn’t want to see the Matrix reset and himself reassimilated. Perhaps the most tantalizing element is the inclusion of Trinity, who spends the bulk of the film trapped in the Matrix as a woman named Tiffany. The only characters that I’d consider “fan service” are glorified cameos: The Merovingian (Lambert Wilson), Sati (Priyanka Chopra Jonas), Captain Niobe (Jada Pinkett-Smith); though in each case they serve a function, whether narrative or commentative. In any case, for large swaths of the film the action is carried by Bugs (Jessica Henwick), along with fresh faces that Wachowski had worked with on Sense8, including Max Riemelt, Brian J. Smith, Freema Agyeman, Eréndira Ibarra, Michael X. Sommers, and Toby Onwumere.

The most brilliant conceit of Resurrections is that Wachowski’s reluctance to make it is baked into the text. Thomas Anderson, a wildly successful if jaded game designer, has everything he could want. Corner office, interns, critical adulation. Although spiritually lost, when presented with the possibility that his world may unravel once again, he resists and flees to his blue pills. His last mental break ended with him walking off a highrise during a party and he’s not ready to brave those waters again. We can draw a rough analogy here between Anderson and modern audiences who lapped up the original’s brilliant action but now just want more comfort food, not another mind-bender. While watching Resurrections, I kept trying to think of another film that achieved a similarly eerie tone in which it seemed as if reality was remixed and our protagonists soldiered onward with only vestigial memories of their past lives. I may be offbase in my comparison because it’s been a while since I’ve seen it, but I finally realized I was thinking of Twin Peaks: The Return, a series which similarly subverted expectations and questioned its own existence. Instead of an easy trip down memory lane, Wachowski (along with co-writers David Mitchell and Aleksandar Hemon) forces the audience to ask meta-textual questions about the pitfalls of rabid fandom, the ability for fictional storytelling to convey truths, and the possibility that what we consume might warp our conception of reality. That Thomas Anderson has grown increasingly reluctant to pull at loose threads in his personal narrative makes him a suitably relatable character in an era of rampant “fake news.”

In other areas, too, Resurrections is stripped of its Matrix-ness, and this is where some may step off the ride entirely. Gone are the iconic action compositions that bore stark resemblance to comic panels. Gone is the iconic green and black color scheme that created a definitive line between the Matrix and the real world. In their place are loosely choreographed fight scenes that do not inspire and “Synthient” programs that embody themselves outside of the Matrix. The story also feels slightly compromised, relying on a pile of contrivances that situate this installment as a deus ex machina love-conquers-all narrative. But even so, with the critiques already firmly understood, perhaps these missteps can be read as a further parody of the franchise symptoms it is deconstructing. Regardless, the focus on Neo and Trinity’s love as a transcendent unifier is the perfect remedy to the afflictions that the story deals with and provides a human element for audiences who just want a compelling story and will disregard all the meta commentary. Indeed, if my wife were to read what I’ve written here, she probably wouldn’t make it halfway through; but she was “very happy” with the film. This is because Resurrections manages to have its cake and eat it too by offering a critical assessment of the current media landscape on top of a story that passes the sniff test for the audiences that have been duped into consuming regurgitated waste.

The Matrix Resurrections is not exactly a return to form, but it’s at least trying to stand out. At a time when mainstream films seem to be empty and self-congratulatory, Lana Wachowski has made one that flies in the face of the corporatized formula, a brave work that doesn’t force our thoughts back onto itself but encourages us to think outside of the bounds of its story and its medium. While its cinematic merits don’t measure up to those of The Matrix, its metatextual storytelling and provocative questions are worth checking out.

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.