“My name is Miles Morales. I was bitten by a radioactive spider. And for like two days, I’ve been the one and only Spider-Man. I think you know the rest.”

A young man is bitten by a radioactive spider which grants him superpowers… Stop me if you’ve heard this story before. It’s the origin story of Peter Parker, more popularly known by his alter-ego, Spider-Man. But it’s also the origin story of Miles Morales. First appearing in the Ultimate Marvel imprint—an out-of-continuity series set in a separate universe that reimagined classic Marvel heroes for modern audiences—Miles Morales proved popular enough that he was moved into the main Marvel universe at the conclusion of Ultimate. Into The Spider-Verse mashes the origin story of Miles together with those of Peter Parker and Gwen Stacy/Spider-Woman. It’s delightfully frenetic, distinguished by its zany characters, self-awareness, and pop culture saturation, as well as its innovative animation techniques that result in exquisitely rendered visuals which make most conventionally animated comic book films seem bland by comparison. It’s an unequivocal triumph, an unfiltered onslaught of technical prowess and joyful creativity. It’s undeniably the best Spider-Man film ever made, and might even be the best superhero film of all time, unapologetically in love with its source material and unwilling to corral it into anything resembling realism.

The thing is just so staggering alive—brimming with ideas, juggling so many stylistic, textural, tonal, and formal elements, managing to feed them to you in just the right combinations that you remain completely engaged and never find it overbearing, pretentious or preposterous. Spider-Verse was co-written by Phil Lord, one half of the duo who created the remarkable The Lego Movie and 21 Jump Street. (Co-writer Rodney Rothman was also one of three co-directors along with Bob Perischetti and Peter Ramsey.) Like The Lego Movie, Spider-Verse is overflowing with meta-textual playfulness. The fourth wall is broken as a matter of course, the narration is ridiculously self-aware, and, because Spider-Man is so culturally ubiquitous, the script is packed with dozens of little references that have no basis within the bounds of the film but can be understood even by a layman passingly familiar with the Spidey universe and characters. It assumes a general grasp of the heroes, nemeses, themes and tropes of Spider-Man and the superhero genre, and also assumes you are worn down by the repetitious outings of the live action Marvel films.1 The epitome of the pop culture meta-referential style is in the post-credits scene, which utilizes the “Spider-Man Pointing at Spider-Man” meme to great effect.

The voice cast is superb, capturing untold nuances in the intricate script, imbuing the film with humor, pathos, and wit. Shameik Moore voices the angsty Miles, an Afro-Latino teenager who chafes at attending a boarding school instead of the “normal” school where all his friends spend their days. He slap tags his sticker art all over the city, listens to hip-hop music,2 and gets along well with his Uncle Aaron (Mahershala Ali). His father (Brian Tyree Henry) does not approve of his son’s behavior or the vigilante justice meted out by the friendly neighborhood Spider-Man. One night, while struggling under the weight of his parents’ expectations and an essay assignment at school, Miles creates some small-scale graffiti in his notebook. At the prompting of Uncle Aaron, the two trespass into an abandoned subway station where Miles throws his creation up on the wall. “No Expectations” it says, riffing off of his assignment on Great Expectations. As the duo work, a radioactive spider gradually makes its way up through Miles’s clothing before sinking its fangs into his flesh.

The story of Peter Parker—two of them actually—literally bursts through the seams of interdimensional reality and into the world of Miles Morales. After his new abilities cause an extremely awkward moment with his new classmate Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld) and Miles discovers that he can walk on walls, he returns to the site of the spiderbite to find Spider-Man (Chris Pine) fighting with Kingpin (Liev Schreiber) in the chamber of a particle accelerator. Kingpin is using the machine to access parallel universes where his dead wife and child are alive and well (an oddly compelling pursuit for a comic supervillain), but things go awry when Green Goblin shoves Spidey’s head into the collider. It’s a wonderfully subversive scene, as the idealistic, super-competent Spider-Man makes plans to train Miles as his protégé, only to have his head beaten to a pulp by Kingpin moments later as Miles cowers in the shadows.

At the grave of Peter Parker, Miles meets… Peter Parker (Jake Johnson). But not the one who he had seen die; this one is a washed up, scruffy, dad-bod Peter Parker who only reluctantly agrees to mentor the young Miles and feeds the audience a steady stream of hilarious lines. But something’s wrong—Peter is not in his home dimension and his body visibly glitches frequently. He will die of cellular decay if he remains in this dimension, a fact confirmed to them by Doctor Olivia Octavius (Kathryn Hahn) when they infiltrate the Alchemax research lab looking for the super collider schematics in order to replicate the “goober” (USB flash drive) that must be inserted to shut down the device. (The plot is intentionally “generic” with Peter repeatedly pointing out that he expects things to work because that’s how they conventionally play out.) They are rescued by Gwen, who reveals herself to be a transplant from yet another dimension brought into Miles’s world during the super collider incident.

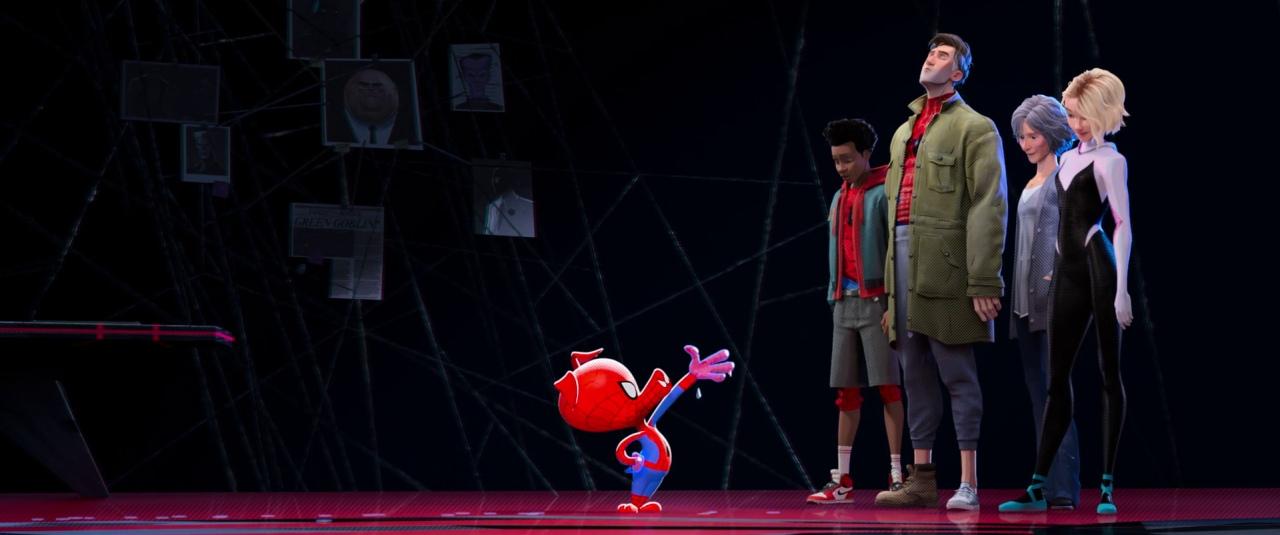

Then things get whacky and super meta. Since all the characters know the history of Spider-Man, they decide to go to Aunt May’s house, where they find she is harboring three additional Spider-People from alternate dimensions who are all experiencing the same glitchy symptoms: Spider-Man Noir (Nicolas Cage), a monochromatic, Humphrey Bogart-like character from the 1930s; Peni Parker, a far future anime character who co-pilots a biomechanical suit with a radioactive spider; and Peter Porker, AKA Spider-Ham, an anthropomorphic spider who was bitten by a radioactive pig (you read that right). The presence of these characters throws a bit of tonal monkey wrench into the film—things weren’t exactly serious or believable or realistic prior to their introductions, but it was a bit of a shock to see them go so far into absurd territory here.3

The plot continues with Miles growing into his superpowers, ensuring his Spider-pals are all returned to their home dimensions, and reconciling with his father. Its climax is a sustained psychedelic fight inside of the super collider that has more in common with The End of the Evangelion than any of the conventional super hero films I’ve seen.

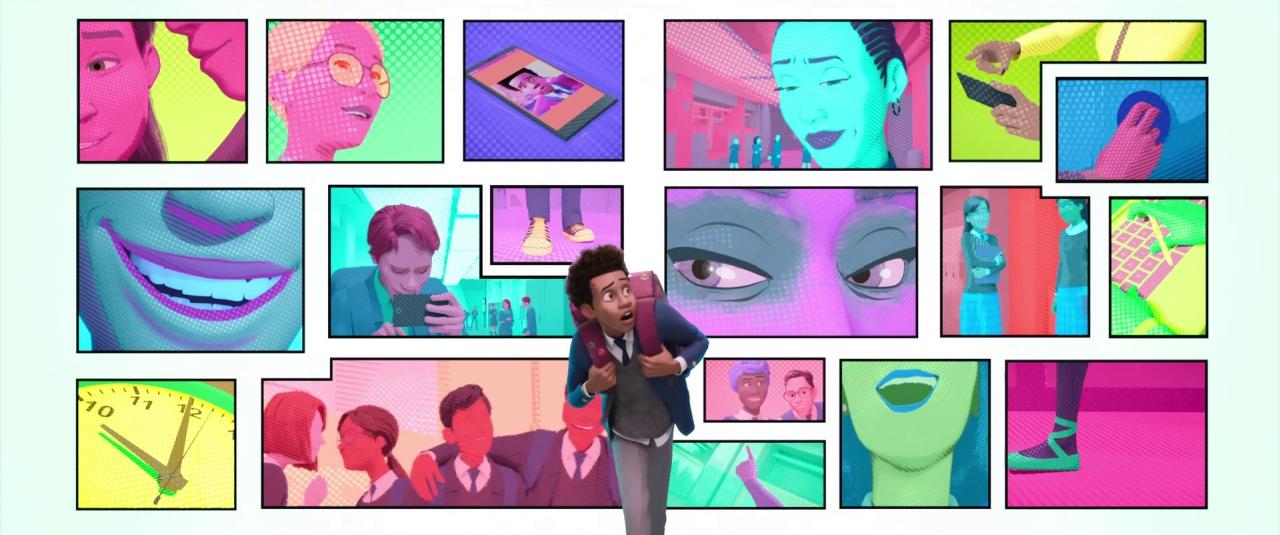

I was enamored with the art style throughout Into the Spider-Verse. It’s somehow both retro and futuristic at the same time. Tactile comic book elements are utilized throughout that give the visuals an authenticity that remains true to its medium of origin—panels, on screen onomatopoeias,4 misaligned colors to mimic slightly misprinted comic book pages, halftone dots and criss-crossed lines to represent varying shades of color and texture, etc. These are all integrated with legit 3D CGI, varying framerates, and different animation styles for each extra-dimensional character. Although you could watch the whole film and not realize that it is breaking new ground and pushing the envelope on what is possible in animated features, this is essentially a feature length, big-budget experiment.

It’s a minor miracle that any superhero film can stand out from its peers in such a crowded market. With few exceptions—Ragnarok, Logan, Deadpool—the genre has steadily suffered in the quality department since Iron Man and The Dark Knight in 2008. Almost all of them feature generic plots, minimal creative flourishes, and come off as very workmanlike—which is fine, because Warner. Bros and Disney are in the franchise business; they know people will pay to see these movies even if they’re the same old thing time and again. But so many of them are simply “part of the whole” and fail to have much utility outside of their part in the overarching storyline of their connected universe. To see such a daring standalone film is refreshing, that it came from Sony makes its unconventional style even more remarkable and commendable.5

As a general rule of thumb, I tend to shy away from reading too much into the political posturing of a film unless it actually pertains to what’s happening on screen. I find that films that use progressive credentials as their calling cards—the entire main cast is female, etc.—often miss the point of cinema entirely because they’re concerned with kowtowing to the agenda instead of making a good movie. The vast majority of explicitly Christian movies fall victim to this as well. No matter your view of “the message” within them, these are simply not good films. Weaving social, religious, or political issues into the texture of a film is possible (e.g. Do The Right Thing, Moonlight, First Reformed) but the issue itself isn’t what hooks the viewer or results in an engaging film; for that you need the things you normally associate with a good movie—storytelling, acting, cinematography, set design… I think you get my point. Anyway, I say all that because there was controversy regarding Miles Morales as a character when he was first introduced in the comics. Some said that the character’s race was changed simply to check a box, like how an H.R. lady gets her bonus for meeting her quota of “diversity hires.” Others claimed that making Spider-Man black wasn’t enough; that the answer wasn’t Miles Morales, but a black Peter Parker. While I’m not very familiar with the comics version of Miles, it seems like the topic of race was eventually confronted pretty bluntly by writer/co-creator Brian Michael Bendis, a move that caused further controversy because he was a white author “speaking for” a minority. Skillfully maneuvering these tricky waters, Into the Spider-Verse integrates its mixed-race lead, Spanish speaking characters, and gender swapped supervillain into the story with remarkable self-assurance. While elements that celebrate diversity are certainly prominent, the film is emphatically not about those things. That Miles creates street art and listens to hip hop are decidedly incidental details in the story—part of the off screen formative years of the character, worked into the script without calling undue attention to themselves. It affirms Miles’s atypical upbringing yet refrains from making that a trite focal point. The achievement of a black Spider-Man—which is not without significance—is secondary to the film itself being great. Having diverse characters included prominently in great films (or having them work in any capacity on the film) is much more important culturally than trying to shovel the message of diversity down the audience’s throat in a mediocre film. Anyway, off my soapbox.

I’ve watched a healthy number of superhero films since they’ve exploded in popularity. I even liked them before they were cool, believe it or not. And I honestly still like them, but, aside from a select few, the best of them are merely “pretty good.” Into the Spider-Verse is one of those select few that deserve to be singled out from among its peers. It is a film where many unique elements were formed together into something that is greater than the sum of its parts. Its scatterbrained narrative shifts, eye-popping visuals, and relentless passion make it a complete joy to watch. It’s a game-changer for comic book films and probably animated films in general.

1. This opportunity for screenwriters to draw on a shared baseline knowledge that virtually the entire audience has is one of the few things that is uniquely interesting about large franchises that can’t be found in standard cinema. This ability to reference lore from the extended universe, without actually bringing those elements on screen, creates an intriguing effect, and it’s only possible once you’ve gone through several iterations/adaptations/versions of it.

2. I don’t have any real complaints about the film; none that hold water, anyway. If I am allowed to nitpick, I’d say that I was a little bit disappointed in the song choices. They probably accurately approximate what a Brooklyn teen would be listening to in the current era, but the soundtrack may not age as well as the rest of the film. Many of the songs fit perfectly fine (and they also shelled out to get Biggie’s ‘Hypnotize’ on there, which was cool), and the score is excellent, so my complaint is a minor one. I just thought that there are better songs within the selected genres that have a bit more staying power.

3. I think it is important to note that all three of these novelty characters actually exist within the comics in some fashion, i.e. none were created specifically for the film.

4. One supremely confident example is when Peter tosses a bagel—stolen from the Alchemax cafeteria—and it doinks off a generic bad guy and “BAGEL!!!” pops up in white letters above his head.

5. There’s a very complicated relationship between Sony and Marvel regarding Spider-Man and related characters on the silver screen. Before Marvel had its own film studio and superhero films became ubiquitous, they sold the rights to Spider-Man to Sony, with a contract stipulating they would retain the rights as long as they released a new film every five years. Several billion box office dollars and a budding “cinematic universe” later, and it became a problem that Spider-Man couldn’t be part of the Marvel equation. They reached a truce in 2015 that allowed Spidey to appear as a guest star in Marvel films while Marvel co-produced the solo Spider-Man films for Sony.

Sources:

Amidi, Amid. “If We Could Do Anything Our Own Way, What Would We Do?: A Conversation With ‘Spider-Man’ Co-Director Bob Persichetti”. Cartoon Brew. 18 December 2018.

Wiggan, Alex. “Who owns Spider-Man: Sony or Marvel?. Don’t Tell Harry: Spiderman Movies Blog. 4 January 2020.