“Wait till you been here a couple years. Give it time, boy. You’ll find yourself doing a hell of a lot of things you’d maybe rather not do in an ideal world. Well, this isn’t an ideal world so you do the best you can.”

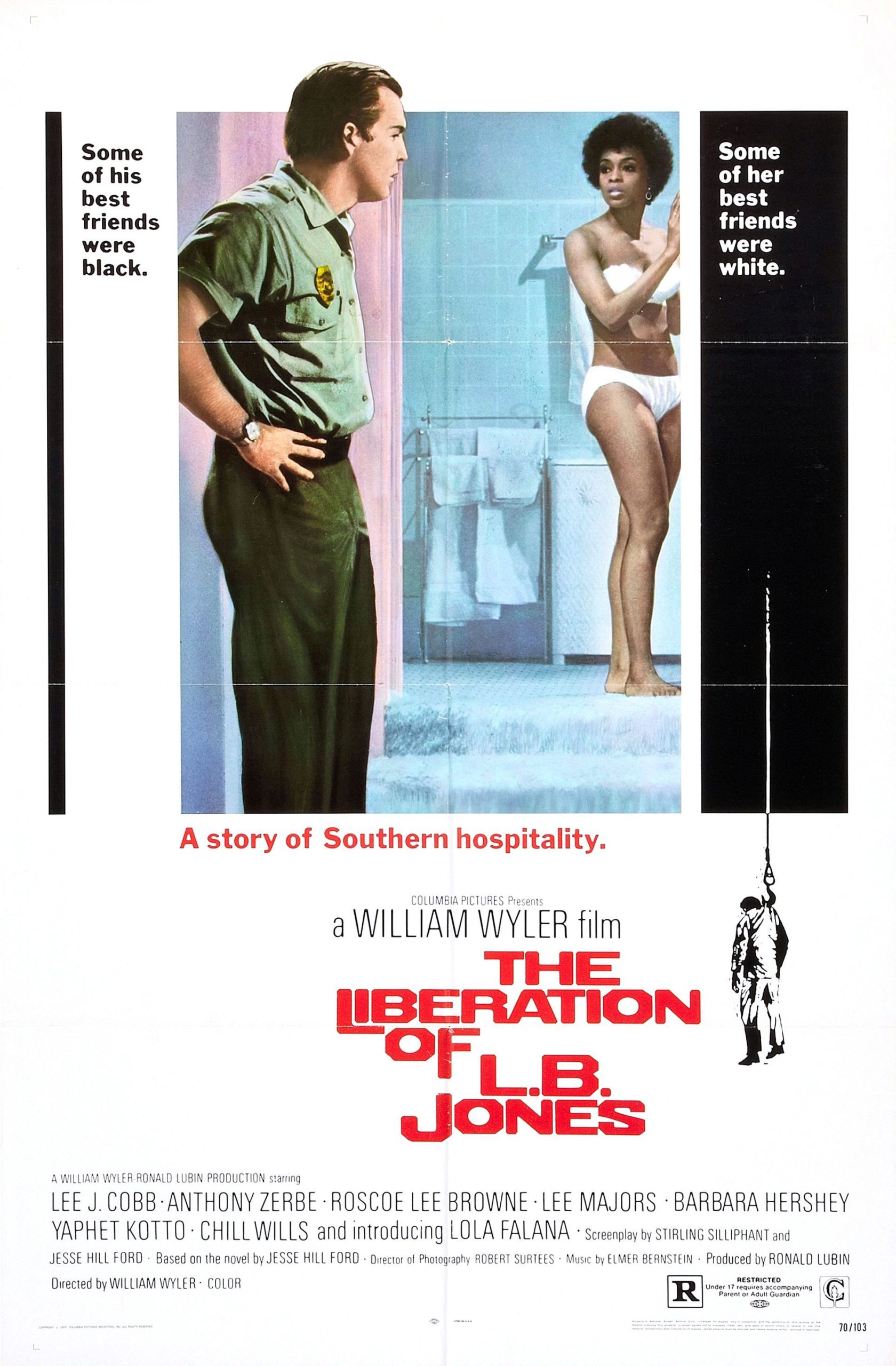

William Wyler’s swan song is one of several race-relations pictures released in the wake of In the Heat of the Night. Like Norman Jewison’s Oscar-winning film, The Liberation of L.B. Jones is a Stirling Sillphant-penned thriller about the hazards of a black man seeking justice in the South. Unlike that watershed effort, however, Wyler’s film lacks any hint of congeniality between whites and blacks as it navigates a divorce case involving interracial infidelity; nor is there a big star like Sidney Poitier to bridge the gap. Because of its bleak vision and lack of big name draw, it didn’t have the same commercial viability nor has it been as culturally relevant in the intervening years as In the Heat of the Night. That’s a shame because it is invigorating to see Wyler—a director who cut his teeth in the silent era—expanding his voice as both an entertainer and a social commentator in the post-Hays code era. In his twilight years, he adapts to the New Hollywood vernacular with verve by employing a pleasantly loose style and integrating previously-verboten levels of sex and violence, resulting in a final film that is uncompromising and unsettling, and undeserving of the lukewarm reception it received upon release.

Lord Byron Jones (Roscoe Lee Brown) is something of an anomaly in the fictional town of Somerset, Tennessee—he’s a rich black man. Well mannered, drives a Cadillac with A/C, dresses in fancy clothes, sexy young wife at home. He is grudgingly respected in the community for his services as the town’s undertaker, a lucrative business that allows him to provide affordable prices to the poorer residents, many of whom are black. He has navigated the racial tensions of the era and bootstrapped himself to success, but all is not well. His nubile wife Emma (Lola Falana) has been seeing a redneck cop named Willie Joe Worth (Anthony Zerbe) and refuses to grant L.B. a divorce. Jones approaches an influential lawyer, Oman Hedgepath (Lee J. Cobb) to represent him in court. Initially reluctant to accept the potentially scandalous case, Hedgepath eventually agrees to it so that L.B. will not seek representation from Hedgepath’s liberal-minded nephew and new law partner Steve Mundi (Lee Majors—one begins to wonder if bearing the name Lee was a prerequisite to landing a role in the film). As he confesses to his nephew, who formerly looked up to him as a role model, he’s had to make moral compromises to build a successful law practice and it would not behoove him to upset the warped social equilibrium of the town by exposing an officer of the law with a young family. On balance it’s clear he’s more interested in protecting the interests of the white community than those of his client.

We do not learn the origin of the affair and by the time of the film’s story it has evolved into an open secret. Indeed, when Hedgepath accepts Jones’s case, the first action he takes is to track down Willie Joe and privately implore him to fix the situation by either ending the affair or convincing Emma to accept an uncontested divorce. But what incentive does Emma have for allowing the divorce? Her passive husband has allowed it to go on so long that she’s grown accustomed to living in luxury as the wife of a wealthy man while simultaneously enjoying the illicit pleasures of an affair. And now that she’s pregnant with Willie Joe’s baby she will need the financial stability Jones affords. When she refuses to allow the divorce to proceed uncontested, a hot-tempered Willie Joe beats her bloody. He then approaches Jones himself—who, keep in mind, has just had to nurse his beaten wife—asking him to drop the divorce case. His impassioned plea is met with indifference from the mortician. Later, in the dead of night, ripped from his car and held at gunpoint by Willie Joe and his partner Bumpas (Arch Johnson), L.B. still refuses. He is shot dead, his body mutilated and hung from a hook in a junkyard to make his death look like a revenge killing at the hands of another black man. In the aftermath, disturbed by his partner’s gleeful slicing and dicing of Jones’s body, Willie Joe confesses to Hedgepath that he executed Jones, but not without implying Hedgepath bears some responsibility for encouraging Willie Joe to avoid the courtroom at all costs. It’s a huge mess, but not one that the seasoned lawyer can’t clean up, especially now that his own neck is on the chopping block.

The film begins with Sonny Boy Mosby (Yaphet Kotto) hopping off a freight train as it rumbles into Somerset. Bearing a revolver hidden in a cigar box, he plans to enact revenge on Bumpas for a brutal harassing when he was only a child. Though he pulls back on his first attempt to kill the racist cop, the death of Jones instills him with a righteous anger and removes any compunction when he shoves the man into the spinning blades of his own baling tractor. The side story is not integrated into the main plot to a satisfying degree, but the death of Bumpas is the only narrative balm we get; the only “liberation” that L.B. Jones will receive. A modicum of additional solace comes when Hedgepath’s nephew and his wife (Barbara Hershey, sadly underutilized), disgusted by his biased behavior and lack of shame, abandon their plans to live and work in Somerset.

The entire film is littered with instances of racial injustice, some of it subtle like Hedgepath’s machinations or a store clerk trying to take advantage of Sonny Boy, but more often it’s blatant—nonchalant use of the forbidden slur; reference to black men of any age as “boy”; sexual pursuit of young black women through violent means; arrests on phantom charges. In the aftermath of the slaying of L.B. Jones, the viewer might expect that, like In the Heat of the Night, there would be a reconciliation. But we are denied a hopeful ending. Like a puppy’s owner rubbing its nose in its own waste on the living room floor, Wyler follows the death of Jones with racist crimes even more heinous and openly hostile than those preceding it. Emma and another anonymous black man are arrested for murder, their confessions obtained at the end of a cattle prod; Hedgepath disposes of the murder weapon and clears any legal hurdles; the mayor (Dub Taylor) washes his hands of the situation; neither officer is held accountable for their actions despite Willie Joe’s obvious remorse. The lack of a positive ending was discussed by Silliphant in an interview:

I was up to my gills with the prevailing wisdom that race relations in the USA were now okay. When, in fact, the only thing that changed was their delusion that they had at last accepted any person of a different skin color or ethnic background as a fellow human being. The film is unremitting, inexorable, without pity or compromise or solution. It simply states that hatred prevails.

The film is based on a novel by Jesse Lee Ford, co-credited with Silliphant for the screenplay. He based the town of Somerset on his own hometown of Humboldt and the central crime on a similar one that occurred there. The residents didn’t like that he exploited their shame and he began to receive death threats, becoming a pariah in his own town. Anxious and armed, potentially inebriated, he shot and killed a black soldier who had innocently parked in his private driveway when he became lost while out for ice cream with his cousin and her child. After a long trial, he was acquitted, brutally reinforcing his depiction of injustice. He died by suicide in 1996.

With a half dozen principal characters and no true protagonist it is understandable that none of them are fleshed out to a satisfying degree. The various storylines occasionally lack focus and are insufficiently integrated, large chunks of exposition are dished out all at once, and several of the performances feel a bit schlocky. It almost seems appropriate to view the violent final act as a precursor to blaxploitation, though the Hollywood sets and studio director dissuade that notion. In any case, the scenes are well-staged and fluid, the pacing excellent, and the foreboding atmosphere effective. But I can understand why general audiences would not have responded well to The Liberation of L.B. Jones. It’s dark, disturbing, and intentionally lacking a feel-good resolution. We can debate the truth of the idea that our society has not changed since the era depicted until the cows come home, but let’s at least agree that Wyler’s final film was overlooked.

Sources:

Gonzales, Michael. “BONE, BLOOD & BIGOTS: ON ‘THE LIBERATION OF L.B. JONES’”. CrimeReads. 11 June 2020.