“I hope that when the world comes to an end, I can breathe a sigh of relief, because there will be so much to look forward to.”

A colossal dud at the box office in 2001, Richard Kelly’s mystical time-traveling debut has gradually increased in stature in the ensuing two decades, and is now considered one of the preeminent cult classics of modern indie cinema. The initial reaction to Donnie Darko is understandable, given Kelly’s dense, multilayered script that shifts between themes, plot threads and cinematic styles in such rapid-fire fashion that it’s nearly impossible to keep tabs on everything in the moment, especially when watching the film for the first time. Though it was filmed prior to the September 11th terrorist attacks, it also features ominous imagery of jet engines and American flags that didn’t sit well when the film was theatrically released just a month later.1 It has garnered a considerable fanbase in the intervening years, the kind that will spend dozens of hours rewatching the film, breaking down its contents, formulating timelines and explanations, and posting their analyses in novella-length forum posts. In this way, it’s not dissimilar to other mathematically precise indie favorites like Primer or Memento. But it’s also deliberately mysterious, with myriad loose ends and esoterica, such that it feels more akin to things like Mulholland Drive, Synecdoche New York, and The Tree of Life—which make more poetic and symbolic sense than strictly logical.

Donnie Darko is about a neurotic teenager (Jake Gyllenhaal) who experiences daylight hallucinations of a six foot tall demonic bunny rabbit named Frank, a mysterious entity who spiritually guides him to commit destructive acts such as flooding his high school and burning down the house of a motivational speaker. As the film goes on, Donnie begins to realize that he is living in what is called a “tangent world,” and that the primary world—the universe as we know it—may implode when the two collapse back into one another. The ins and outs of this have been dissected by many people who have spent a lot more time pondering how all of it fits together than I have, so I’ll only do a quick recap of the major arc of the film and then discuss other things.

We begin with Donnie awakening in the middle of a road after sleepwalking (or sleep-biking, I guess). From the outset, it is clear that he is troubled. He is distant from his family members, his mother wonders aloud where he goes at night, and he is intentionally instigative toward his sisters, Sam (Daveigh Chase) and Elizabeth (Maggie Gyllenhaal, Jake’s real life sister). Soon after Elizabeth reveals that Donnie has stopped taking his pills, our frustrated, purposeless protagonist wanders into the night where he meets Frank. Frank tells him that the world will end in 28 days, 6 hours, 42 minutes, 12 seconds. Awakening the next morning on the green of a local golf course, Donnie finds the numbers written on his arm in unfamiliar handwriting. When he returns home, he discovers that a jet engine of unknown origin had crashed through his bedroom during the night.

With the family living out of a hotel, Donnie’s nocturnal excursions grow increasingly erratic. He befriends Gretchen (Jena Malone), the new girl at school, who also suffers from feelings of social alienation and is not scared off by Donnie’s antics and mental issues. Gretchen is important to the story because while Donnie mostly feels disdain for every other person, he comes to love Gretchen, which allows him to by extension feel love for everyone; this is key to Donnie’s redemptive arc. Prompted by Frank, Donnie asks his physics teacher, Dr. Monnitoff (Noah Wyle) about time travel. Monnitoff gives him a book called The Philosophy of Time Travel, which was written by Roberta Sparrow (Patience Mather Cleveland), a former nun who had also taught at Donnie’s school before becoming the reclusive “Grandma Death” (we encountered Grandma Death a few scenes earlier when Donnie and his father almost ran her over in their car). The book is kind of like the picture on the box of a jigsaw puzzle that guides the audience as they put all the puzzle pieces together. Throughout the film, excerpts from the book, presented on screen, help to explain the formula behind tangent universes, catalysts, artifacts, glitches in time, etc. The contents of the book convince Donnie that his sleepwalking adventures occur in a different strain of time, or in an alternate universe.

In the film’s climax, the entire narrative is rewound, putting us back to the moment of the glitch when the jet engine fell from the sky. This time, Donnie is awake, lying in his bed and laughing as the chunk of metal demolishes his bedroom. The film’s concluding shots, rolling while a cover of ‘Mad World’ plays, show those whose lives Donnie has touched—some of whom, like Gretchen, have not met Donnie in this timeline—having some kind of spiritual experience. They sit up in bed, crying and disturbed, without anything to prompt their unease. Gretchen and Donnie’s mother (Mary McDonnell) share an awkward wave as Mrs. Darko smokes a cigarette while contemplating her son’s death.

While we watched the film, my wife—who loves to offer her end-of-film predictions throughout a film’s runtime—continually predicted that the film was all taking place in Donnie’s head. Some people interpret the film as Donnie’s spirit reconciling itself to death in the split-second before the engine crashes through his bedroom, while others tend to view the whole thing through the lens of Donnie’s mental illness. But I think those interpretations strip it of too much of what makes it special. He is clearly disturbed—he is to the point where his therapist is regularly hypnotizing him—but that’s only an incidental avenue to get at the themes that Richard Kelly was really aiming for here.

Though we never learn why Donnie specifically was chosen, Roberta Sparrow’s book sheds enough light on the situation for Donnie to understand that he has been selected as the “living receiver,” one tormented by dreams and hallucinations, granted fourth dimensional powers, and given the responsibility for returning the “artifact” to the primary world. Another clue in the book is that the “manipulated living,” and the even more powerful “manipulated dead” (those who die in the tangent universe) will do anything in their power to prevent their own destruction, allowing us to see these random events as divinely orchestrated occurrences arranged to prevent the annihilation of the universe. It’s never made clear exactly what divine agent is in control of these events, but Donnie’s acceptance of his role as a kind of sacrificial Christ figure certainly points a finger in a certain direction (with other confusing indicators thrown in to shroud the whole thing in mystery).

I really enjoy the surface level story. It has a nice balance of realism and mysticism—we feel like the cinematic world we’ve entered has enough similarities to our own that the events we see are happening to real people. The elements of comedy and teenage drama help in this regard. As I stated earlier, the film’s mathematical precision has been pored over by many dedicated fans, and if there are inconsistencies I’m sure they’ve been pointed out. But I don’t really care if there are logical gaps, because the film isn’t exclusively about time travel; it’s about determinism and the existential question of free will—not exactly the kind of thing that a filmmaker usually tackles in their directorial debut, especially when they’re working in genre cinema.

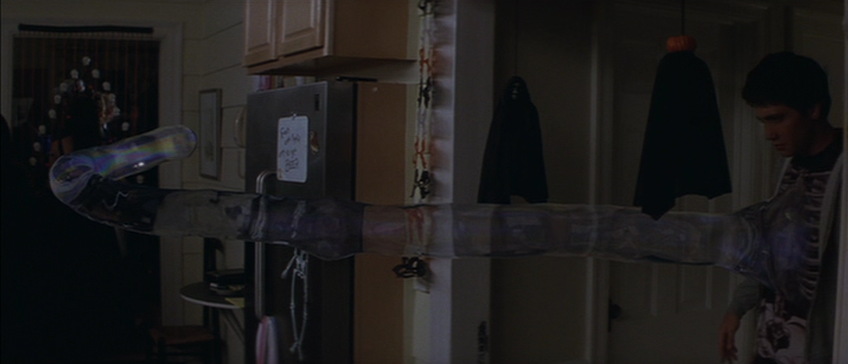

Despite the powers granted to Donnie as the living receiver (he can see where people will be before they move to occupy that space, he can lodge an ax into a bronze statue) his question to Frank, of why the world will end in 28 days, 6 hours, 42 minutes, 12 seconds, is never answered. We’re given a glimpse behind the curtain to view the mechanism by which it will end, but the fundamental question of why remains unanswered. We also never learn why the responsibility of rectifying the situation has fallen on Donnie’s shoulders. Though the concepts of philosophy and physics are drawn from ideas fleshed out by real philosophers and scientists, Kelly wisely obscures these things.2 Rather than explain away all of the mystery that was introduced in the film, Kelly leaves things unresolved, because that is key to the film’s main moral—that our own understanding of the universe is limited, that we’ll never comprehend the world we were born into and the trajectories we were already on before we became aware that we could choose things. To Donnie, this seems to mean that he may not have a choice at all. Although he appears to be acting in accordance with his own warped desires, his viewpoint is limited and he is keenly aware that outside forces that he can’t comprehend are at work in the world.

Throughout the film, Donnie’s attempts at a deeper understanding of the universe do not bear fruit. There is a subplot involving a spiritual guru named Jim Cunningham (Patrick Swayze) who steals the hearts of the suburban moms, especially that of gym teacher Kitty Farmer (Beth Davis). His self-help videos promote the idea that every choice, thought, and action lands somewhere on a dichotomous scale between love and fear, “the deepest of human emotions.” When a classroom exercise prompts Donnie to assess a situation involving the theft of money, and to place that action on a spectrum between love and fear, he goes on a tirade about the futility of reducing human actions to such an insufficient metric. He finds it impossible to interpret his own experiences through such a lens, and struggles to comprehend how actions which he may have no control over could have any moral quality at all. Later, when the guru himself is giving a seminar in front of the whole school, Donnie approaches the Q&A microphone and accuses the man of being the Antichrist.

In a session with his therapist (Katharine Ross), Donnie confesses that he has never seen any proof that he is not “alone” so he chooses not to debate the fact with himself anymore. This cryptic statement can be taken to mean several things, but I think the most plausible is that those he interacts with profess such simplistic worldviews that he cannot meaningfully relate to them. Even Dr. Monnitoff, who had initially discussed time travel with Donnie and given him the book, chooses to end their discussions out of fear of losing his job. In their earlier conversations, Monnitoff had posited that if one could see their future actions, then they would have the choice to change them, and thus exercise free will. But as Donnie comes to understand that he has been chosen to prevent the destruction of the universe, choosing anything but the sacrifice of himself would be completely heinous. Does he really have a choice, if his constitution would not allow him to willingly commit an act that would end the lives of everyone he knows, let alone all of humanity? A Youtuber named Niyat, who produces videos as FilmComicsExplained, compares Donnie’s situation to Baruch Spinoza’s analogy of the stone. He quotes Spinoza in his video analysis (linked below).

Conceive, I beg, that a stone, while continuing in motion, should be capable of thinking and knowing that it’s endeavoring to continue to move as far as it can. Such a stone, being conscious merely of its own endeavor, and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free and would think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. That is the human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined.

In Niyat’s video, he follows the quote with a reversed video of a man skipping a stone, which I think illustrates his point perfectly. In each moment of Donnie’s life—in each moment of our lives—we are making decisions based on limited information, in consideration of our limited abilities, our proximity to other people, and the potential ramifications of our choices. But we came into the story of the world well past its beginning and didn’t choose anything at all about our trajectory. And once each of us became aware of ourselves, we were already moving at such speed, and our predisposition had already been formed to such a degree, that many of our future decisions were essentially already made for us. This is the feeling that creeps up on Donnie, like he knows he is a character in a screenplay of which he is not the author.

As Donnie explores the world unmedicated—which some view as him becoming enlightened in some sense—it becomes clear that everyone around him is searching for a deeper sense of purpose in their lives. The way that so many grown adults latch onto the fear vs. love teachings of Cunningham like they’re some kind of profound revelation is disconcerting to Donnie. This comes through most clearly in the character of Kitty, who becomes something of a disciple of the guru and also projects an inordinate amount of her own psyche into her daughter’s dance team. She is so conflicted that she doesn’t know whether to appear at Cunningham’s arraignment or fly across the country for a televised dance competition. Donnie can see that it is too simplistic and very probably outright wrong to live this way, but he also wishes that he could have the veil pulled back over his eyes and do so; he desires his anxious thoughts and piercing insights to be dulled into a simple-minded system of needs and wants that don’t require an illusion of choice.

While he and his friends chill out in a field and shoot at bottles, they somehow get off on a tangent about the sex life of the Smurfs, the blue cartoon characters. His friends get weirdly graphic about how it all works, and though Donnie’s response is likewise vulgar, it shows that Donnie seems to think that humans (or Smurfs) are geared to put the reproductive act above all else. (I also happen to think it’s one of several very funny moments in the film, which has a very strong mix of humor, horror, and wonder).

First of all, Papa Smurf didn’t create Smurfette. Gargamel did. She was sent in as Gargamel’s evil spy with the intention of destroying the Smurf village. But the overwhelming goodness of the Smurf way of life transformed her. And as for the whole gang-bang scenario—it just couldn’t happen. Smurfs are asexual. They don’t even have reproductive organs under those little white pants. That’s what’s so illogical, you know, about being a Smurf. What’s the point of living… if you don’t have a dick?

Later, in Ms. Pommeroy’s (Drew Barrymore) English class, the students are discussing Watership Down. Donnie echoes his sentiments about wishing to have only the propagation of his species as his single desire, but he also expresses a negative view of such a way of life, suggesting that the death of the rabbit species would not be as sorrowful as the death of humanity. In response, Gretchen echoes Ms. Pommeroy’s assertion that the rabbits in Watership Down are obviously stand-ins for humans, and that since they have meaningful interactions because the author gave them the ability to communicate at a high level, that they deserve empathy.

Ms. Pommeroy: When the other rabbits hear of Fiver’s vision, do they believe him?

Donnie: Why should we care?

Ms. Pommeroy: Because the rabbits are us, Donnie.

Donnie: Why should I mourn for a rabbit like it was human?

Ms. Pommeroy: Are you saying that the death of one species is less tragic than another?

Donnie: Of course. The rabbit’s not like us. It has no history books, no photographs, no knowledge of sorrow or regret. I mean, I’m sorry, Miss Pommeroy. Don’t get me wrong. You know, I like rabbits and all. They’re cute and they’re horny. And if you’re cute and you’re horny, then you’re probably happy that you don’t know who you are or why you’re even alive. You just wanna have sex as many times as possible before you die. I just don’t see the point in crying over a dead rabbit, you know, who never even feared death to begin with.

Gretchen: You’re wrong. These rabbits can talk. They’re the product of the author’s imagination. And he cares for them so we care for them. Otherwise, we’ve just missed the point.

Ms. Pommeroy: But aren’t we forgetting about the miracle of storytelling? The deus ex machina? The God machine? That’s what saved the rabbits.

I don’t know what exactly that exchange is meant to convey, and I think that’s part of what makes it effective. It also works because Donnie is a confused teenager, not a learned thinker who should have considered opinions on these matters. His outburts indicate that he thinks less of non-human species, but also that he envies their unknowning state of mind. In some schools of Christian thought there is a notion that early man didn’t have the taint that afflicts modern man. He was able to live “unconsciously” or “spontaneously,” making the correct choices simply because it was natural to him. This seems to be something like what Donnie’s searching for. This seems to be, vaguely at least, the direction that Donnie’s conversation with Monnitoff is headed before Monnitoff abruptly ends it.

Donnie: Well, if God controls time, then all time is pre-decided.

Monnitoff: I’m not following you.

Donnie: Every living thing follows along a set path. And if you could see your path or channel, then you could see into the future, right? Like, uh… that’s a form of time travel.

Monnitoff: Well, you’re contradicting yourself, Donnie. If we were able to see our destinies manifest themselves visually, then we would be given a choice to betray our chosen destinies. And the mere fact that this choice exists would make all preformed destiny, uh, come to an end.

Donnie: Not if you travel within God’s channel.

Monnitoff: Um, I’m not going to be able to continue this conversation.

Donnie: Why?

Monnitoff: I could lose my job.

Eventually, Donnie comes to accept that he will not understand much of anything, but that his life still has a purpose. To wit, all of his angst and discontentment and mental troubles resulted in him making choices that led him to save the world. Though he fulfills the role of a sacrificial lamb in the film’s conclusion, Donnie is far from a standard Christ figure. In his seminar, Jim Cunningham warns of three chief traps for teenagers—sex, drugs, and alcohol—Donnie partakes of all three. But, as Christ taught, those who exalt themselves shall be brought low, and those who humble themselves shall be exalted. Such is the case with Cunningham, whose “kiddie porn dungeon” is exposed when Donnie burns his house down; and Donnie, whose forfeit of control results in smiling acceptance as he fulfills his purpose. The exaltation of Donnie, of course, would not happen in the here and now. This idea of postponed glory is symbolically represented by Cherita (Jolene Purdy), a chubby Asian girl who is routinely put down by bullies but performs a dance at the talent show while dressed as an angel.

I don’t think that Richard Kelly sat down and logically pieced this together. It’s too rangy to be the work of a “professional,” as it careens from hilarious to serious to mystifying. Rather, I think he was personally entranced by these themes of time travel, physics, wormholes, and determinism, and just started writing, and this is what came out, only shaped into a cohesive story once much of it was conceived. Fresh out of film school, Kelly set out to write something “ambitious, personal, and nostalgic about the late 80s,” citing surrealist filmmakers Peter Weir and Terry Gilliam as key inspirations. Like the mysterious films of David Lynch, Donnie Darko is imminently engaging but can never be gathered up into a sensical whole. It’s a messy exploration of themes and ideas that were bubbling around in the mind of a bold young filmmaker. And that is oftentimes a recipe for a groundbreaking, refreshing experience. I’ve seen the film a handful of times now, and each time I watch it, the things I consume in its wake just seem bland in comparison. It’s an explosion of creativity that doesn’t often see the light of day or receive a substantial enough budget to be made well. The ideas and philosophical conundrums that are investigated have been mulled over by many smart people for a long time, and the answers will probably always remain outside our grasp, but they’ll always remain enthralling subjects to think about, and the mysterious way they are presented here is completely mesmerizing to me.

Like the greatest cinematic achievements, Donnie Darko makes full use of its medium. There are numerous moments where sound, image, editing, and acting are used to brilliant effect, but there is one that stands out to me as particularly memorable. Donnie and Gretchen are in a movie theater, alone, watching The Evil Dead. As Gretchen falls asleep, Donnie looks beyond her to see Frank sitting on her opposite side. A powerful, elegiac piece of vocal music begins to play as the two have the film’s most iconic exchange: “Why do you wear that stupid bunny suit?” “Why are you wearing that stupid man suit?” It’s chill-inducing stuff, and reinvigorates my love for the unique ability of cinema to combine the talents of so many people into something beautiful, haunting and transcendent.

Reading back over my own words, which I’ve done five or six times now, I still don’t think I’ve adequately captured the wondrous experience that this film has provided for me time and again. But, considering how I just made the point that film is uniquely positioned to do that as it combines sound and the moving image, I guess I can’t really expect mere words to convey just how magnificent and entrancing it really is.

1. Note that I’ve watched the director’s cut more times than the theatrical version, so that’s more or less what is being reviewed here.

2. There are legitimate theories of time travel, but none of them have worked yet, so it would be silly to criticize the director of a science fiction film in which time travel actually occurs for not committing to a concrete explanation of what’s going on.

Sources:

“DONNIE DARKO | The Meaning and Philosophy | EXPLAINED”. Youtube, FilmComicsExplained. 8 November 2020.

Kelly, Richard. Interview by Jason Korsner. BBC. 25 October 2002.