“It’s probably nice to know your parents were once not your parents.”

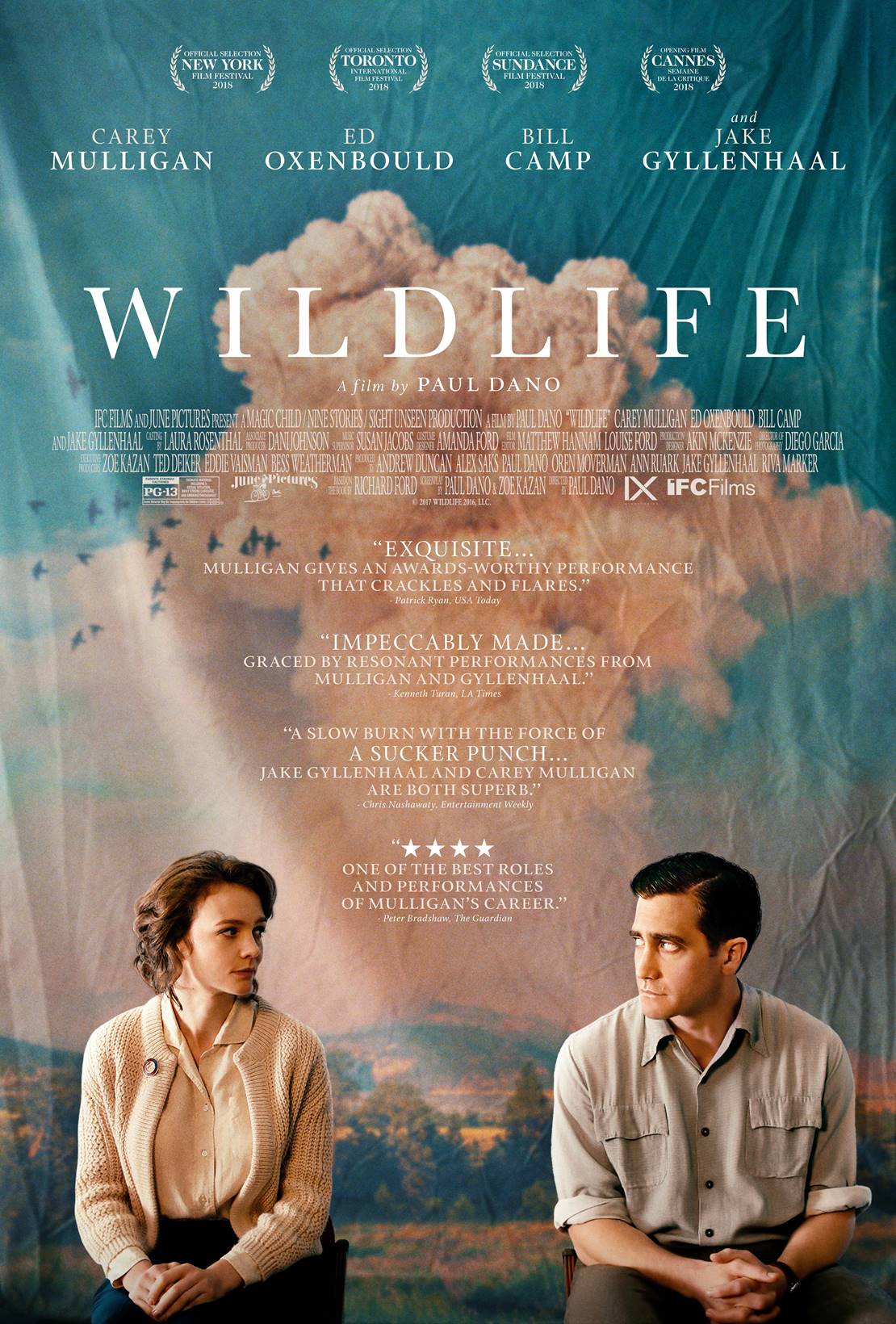

When Jerry Brinson (Jake Gyllenhaal) is laid off from his job as a golf pro, he elects to take a job fighting the wildfires ravaging rural Montana for a dollar an hour; a rash, reckless decision that leaves his wife Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) without a husband and his son Joe (Ed Oxenbould) without a father. In his absence, Joe awkwardly struggles to self-actualize in his 1960s suburban environment, quitting the high school football team and taking up part-time work at a local photography studio in a futile attempt to be the man of the house.

Psychologically rattled, Joe’s mother impertinently discusses her marital issues with her son—almost testing him in a sense, to see if he might suffice as an unnatural stand-in for her mate—before covertly falling into the arms of a prosperous car dealer (Bill Camp) whom she taught to swim at the YMCA. He can offer the material comforts that Jeanette craves, but even as she goes through the motions of the affair her paper-thin optimism fools no one, least of all herself. When Jerry returns, their reunion is charged with animosity, regret, and bitterness that turns to deep melancholy some months later when the broken family sits together for a portrait.

Throughout Wildlife, the directorial debut of Paul Dano, co-scripted with his partner-and-mother-of-his-children-but-not-wife Zoe Kazan from the novel by Richard Ford, the Brinson’s crisis is symbolically represented by the wildfires consuming Montana’s forests. Early in the film, a park ranger informs us that forest fires can be beneficial; that the subsequent regenerative growth is crucial to the long term health of the terrain. On the other hand, when Jeanette and Joe drive out to witness the fires that have drawn Jerry out to combat them, Jeanette remarks that the term firefighters use for the trees left upright after the fire is the “standing dead.”

By the end of the film, Dano’s meticulous direction—which gives precedence to character over theme, bravely forgoes voiceover narration, frequently eschews depicting events and conversations in favor of Joe’s silent reaction to them, and uses radio chatter to flesh out the period setting—has delivered a haunting portrait of Joe as a “standing dead” who has been irreparably damaged by his parents actions to such an extent that renewal seems unlikely. He’s a teenager who, in his mother’s words, “doesn’t know what is and what isn’t,” but his timid demeanor and emotive expressions indicate that he sees through his parents’ façades to the confusion and deep flaws they try to obscure, while also suggesting that he will suffer from the same sense of existential insecurity that provided the conditions in which a small spark could lead to utter devastation.

Anchored by strong turns from Mulligan and Oxenbould (Gyllenhaal is fine too but his screen time is limited) and astutely crafted, this intimate drama examining the dissolution of an ordinary nuclear family through the eyes of a child proves that Dano is as natural behind the camera as he is in front of it—maybe even more so, since some of his best acting roles work precisely because of his off-kilter screen presence.