“Perhaps I got a little sentimental. Perhaps I got tired and felt a bit sad. It’s not impossible that I began to think of this and that, associated with places where I played as a child. I don’t know how it happened, but the day’s clear reality dissolved into the even clearer images of memory that appeared before my eyes with the strength of a true stream of events.”

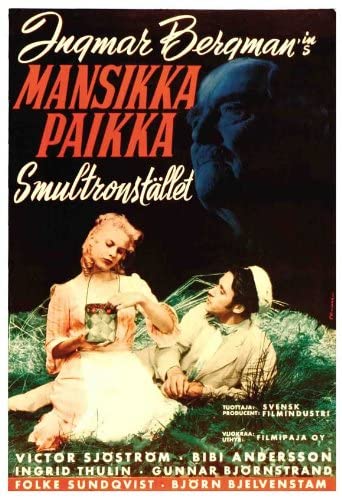

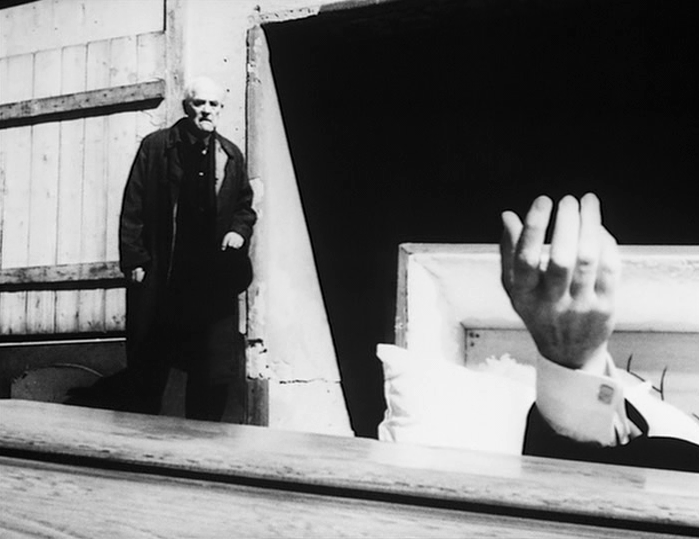

Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries is the work of an artist conscious of his own insecurities and internal torments, exploring inward and piecing together an affecting meditation on regret, mortality, dreams, and the internal struggles we all face. Early in the film, the aged Dr. Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) lies down to go to bed. His sleep is not peaceful, and his physical ailments are mirrored by the anxieties that haunt his dreams. The first dream begins in near silence as Borg wanders the streets of an empty city. The frame flickers inconsistently in imitation of the first cinematic creations at the turn of the twentieth century—an era to which the films of Sjöström (himself a pioneering director of Swedish cinema) belong. Borg is isolated against the boarded windows and doors, the only witness to his trespass the vacant eyes hanging from a handless clock above the street. He is briefly framed in blackness, and then he is not alone, but finds himself in a surrealist dreamscape. He approaches the other wanderer only to find the man’s human face grossly distorted. The man collapses and melts, his crumpled suit emitting an inky liquid from its collar. The soundtrack picks up now, as we hear a carriage approaching, carrying a casket. The carriage gets stuck on a light pole, and the resulting rhythmic screeching turns the dreamer from bemused to frightened. When the carriage breaks free and the horses pull it away, the coffin falls out of the back and breaks open. Borg approaches it, and it is confronted by his doppelgänger, who tries to pull him down into death.

In the waking world, Borg is an aged medical professor and a widower, who, with the bulk of his life behind him, lives with longstanding regrets that inhibit his everyday life in addition to symbolically haunting his dreams. He is to be awarded a lifetime achievement degree to honor his career. Startled awake by his dream, instead of waiting to take a flight to the ceremony—which he regards as largely devoid of meaning and merely obligatory—he decides that he will use the day to undertake the fifteen hour drive through the Swedish countryside, intending to use the time alone to reflect on his past and its forking paths.

The film opens with Borg telling the audience: “In our relations with other people, we mainly discuss and evaluate their character and behavior. That is why I have withdrawn from nearly all so-called relations. This has made my old age rather lonely. My life has been full of hard work, and I am grateful. It began as toil for bread and butter and ended in a love for science.” Throughout his life, he has pushed other people to the periphery as he pursued a life of professional achievement. On his journey to the ceremony, other people—both previous acquaintances and newly met friends—will serve as a catalyst for dreams and the reliving of memories. These recollections of childhood and early manhood bring to the surface a host of unresolved issues that have plagued the doctor throughout his long life, and have shaped the man who he has become; a man that Borg struggles to accept as himself, as he is troubled by guilt, regrets, and a struggle to find meaning in life.

Various memories unfold before us, illuminating the experiences that have etched Isak’s interior life such that he has come to a point of self-inflicted isolation and moral decay. His wife had deceived and humiliated him; his first love Sara (Bibi Andersson) had chosen to marry his brother instead of him. Isak and his daughter-in-law Marianne (Ingrid Thulin) visit Isak’s mother (Naima Wifstrand) partway through the film. Through their cold interactions we glean that Isak may have inherited many of his negative tendencies of pride and ego, and that he may have passed them on to his son, Evald (Gunnar Björnstrand) as well.

During the trip, Isak tells Marianne of his strange dreams, believing that his dreams are trying to tell him that he is dead, even though he is alive. The statement reminds her of a recent conversation she had with Evald, which had occurred in the same car. Evald is sitting where his father sat. Marianne has asked Evald to accompany her so that they can have a conversation, and he is suspicious of what news she wishes to break to him. He suspects that she has found another man, and seems resigned to accept the fact. When she laughs at this suggestion, and tells him that she is pregnant, his reaction is even more fierce than if she had admitted infidelity. His statements betray a lack of belief in any true goodness in the world.

“It’s absurd to bring children into this world and think they’ll be better off than we are.”

“This life sickens me. I will not be forced to take on a responsibility that will make me live for one day longer than I want to.”

“There’s neither right nor wrong. We act according to our needs . . . Yours is a hellish desire to live and to create life . . . Mine is to be dead. Stone dead.”

It is Marianne who notes the hereditary coldness that Isak’s mother showed to him, and how he and his son, Evald, both believe themselves to be dead inside. Both Marianne and Isak consider the Almans—the second set of passengers they had with them that day—who seemed to loathe one another with a passion. Isak recalls his own marriage being much the same, and Marianne fears that hers will end up that way.

The first passengers that Isak and Marianne take on are a trio of hitchhikers: Sara (Bibi Andersson, in her second role of the film), and two men competing for her affections, Anders (Folke Sundquist) and Viktor (Björn Bjelfvenstam). Isak is having a peaceful reverie about his childhood, in which his family is spending one of his childhood summers at their house on an island. He witnesses his cousin Sara innocently picking strawberries, before she is confronted by his brother Sigfrid. He follows the family inside for dinner as they celebrate a birthday party, and the young twins make fun of Sara and Sigfrid’s private encounter. The reverie is broken when the hitchhiker Sara awakens him to ask for a ride.

At lunch, the two men begin arguing about theology. They are on a terrace, enjoying coffee, and Viktor—who plans to become a minister—breaks an agreement between the two to avoid discussing science and God while on the trip. They argue for a moment, and then ask Isak to weigh in on one side of the argument or the other. He refuses to give his own thoughts, instead beginning to recite a poem, which the others help him complete. (The poem is by Johan Olof Wallin, an archbishop of the Church of Sweden born in the 18th century.) For a brief moment in the tumultuous life of Dr. Borg, peace abounds. His stories have been met with laughter, and he is in good company. The group harmoniously take turns picking up the lines of poetry, seeing the stanza through. The scene is a lovely bit of cinematic transcendence.

“Where is the friend I seek at break of day?

When night falls, I still have not found Him.

My burning heart shows me His traces.

I see His traces wherever flowers bloom

His love is mingled with every air.

His voice calls in the summer wind.”

After lunch, as rain patters on the car window, Isak again drifts into dream. He speaks with the ghost of his cousin Sara, at the same spot where his brother had forced himself upon her so many years ago. In his previous vision of her she had lamented, “Isak is so fine and good, so moral and sensitive. He wants us to read poetry and talk about the next life and play four-handed piano . . . and he talks about sin. He’s on such a terribly high level and I feel so worthless.” Now, she has matured; she is not mocking or disdainful, yet she is not compassionate either — she is merely serious now.

“You’re a worried old man who’s soon going to die, but I have all my life before me.” She encourages Isak to smile, and he tries, but it hurts him to do so, and tears well in his eyes. “As professor emeritus, you ought to know why it hurts. But you don’t know. You know so much, and you don’t know anything,” Sara says.

In a Kafkaesque dream, Borg must take part in an examination, which he finds himself incapable of completing. The exam is given by Sten Alman (Gunnar Sjöberg), the hitchhiker who had loathed his wife. Dr. Borg cannot identify the specimen under a microscope, and the words on the blackboard appear as gibberish to him. He misdiagnoses a patient, Berit Alman (Gunnel Broström), as dead, and she wakes up and laughs in his face. The examiner notes that he has been deemed incomptent, and is also being charged with selfishness, callousness, and ruthlessness. (If there is a minor fault with the Wild Strawberries, it is that we never actually see the episodes in which Borg is selfish, callous, and ruthless, we are only told about them.)

In one of the concluding scenes of the film, Isak stands on his balcony as the hitchhikers serenade him with a farewell song. Sara, the doppelgänger of Isak’s cousin, affirms what his dreams have been telling him: that one should not apologize for needing love, and that is should be given without qualification. “It’s you I really love, you know. Today, tomorrow, always,” she says.

He settles into bed for a final dream. In the last scene, back at the summerhouse, the children are looking for their mother and father. Sara offers to help Isak look for them, and together they walk through a field, and she points out toward the shore. There, above the idyllic stillness of the water, sit Isak’s parents: his father with a long fishing rod extended in a lazy arc above the lake, and his mother sitting comfortably on a blanket. His limiting self-mythologizing has ended; he has accepted his past, and although his days are short, he can now live them in peace.