“Well, old-timer, what is it? What’s in the noodle?”

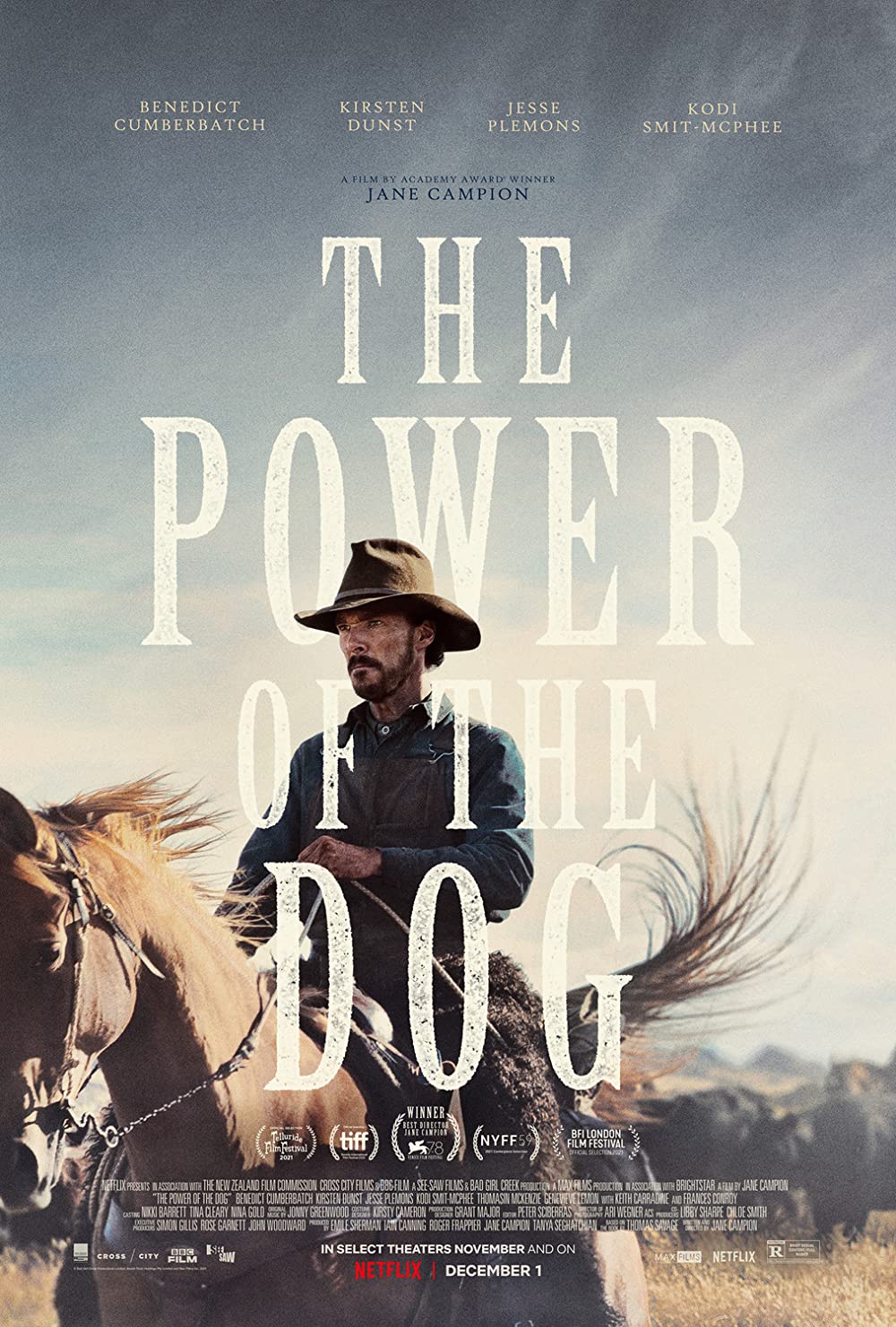

In The Power of the Dog, a homoerotic, psychodramatic Western from Jane Campion, an effeminate young man (Kodi Smit-McPhee) who aspires to be a doctor is brought into proximity of an irascible, closeted cowboy (Benedict Cumberbatch) when his widowed mother (Kirsten Dunst) marries the man’s soft-hearted brother (Jesse Plemons). When the mother and son take up residence in the mansion on the brothers’ large cattle ranch, upsetting the empowering routine established by a quarter century of repetitions, a period of ruthless probing commences during which the mother resorts to alcoholism and the boy seems to form an emotional connection to his performative tormentor. What is the nature of their relationship? Abuser and victim? Mentor and mentee? Uncle and nephew? Romantic equals? While such a premise expectedly calls to mind Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, what first appears as an improbable love story morphs into a tale of slyly orchestrated revenge.

This vastly overrated film, which propelled its director to an Academy Award, sets out to critique the gender stereotypes of the classical Western but finds itself inevitably stuck in the present and thus unable to offer a “revisionist” experience. In its modern dialogue, pristine sets, and general ambience, but most especially its transparently voguish thematic concerns, it fails to transport the viewer into its period setting. Worse, it seems to be working under the assumption that its central character study of a closeted gay man in an unexpected milieu is a fundamentally compelling enough setup that it need not concern itself with cogent storytelling. It suffers the same unevenness that plagues The Piano—some exceedingly passionate or menacing sequences (has a banjo felt this sinister in a movie since Deliverance?), some excruciatingly hackneyed (did we need so many visual innuendos?), some lukewarm, all stitched together into an unbalanced whole and smoothed over by Johnny Greenwood’s effective score—but its moments of intimacy and melodrama do not match those of the earlier film. Too often the decision to include or exclude a narrative event from the screen seems to have been made with only a mind for its symbolic meaning and the film’s 21st century context rather than the needs of the story. The most crippling outcome of this approach is that the characters’ motivations rarely seem real to the viewer and so the film fails to find an emotional throughline.

Though capably acted, shot, and scored, Campion’s episodic film is ultimately reduced to the central question of why Cumberbatch’s volatile rancher feels the need to antagonize. The reductive answer—that toxic masculinity stems from latent, repressed homosexuality—is obvious from the start, rendering the programmatic drama that unfolds across the film’s two hours limp and lethargic, only lifted when the cast outperforms the script. It’s a treat for those who work themselves up into an intellectual frenzy over what films are “trying to say” in lieu of evaluating whether or not they’re worth their salt as works of cinema. Which is to say, it’s much better on paper, where one can talk around its flaws, use its socially conscious message as a sounding board for tangential discussions, and pretend that its tidy yet somehow incohesive story builds to a forceful climax. At the very least it has the courage to not only refrain from redeeming its gay villain, but to outright kill him off just when you think he might be turning a corner, and to have that overcompensatory crime perpetrated by the heretofore sympathetic gay protagonist.

Neither as wrenching nor as revelatory as its creator envisioned, The Power of the Dog nevertheless underscores that genre films offer fertile ground for socially conscious filmmakers. The thing is, though, that the moody, insightful Western has been done much better. Set against films like McCabe & Mrs. Miller, There Will Be Blood, or The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, it is abundantly clear that Campion’s film is far from the masterpiece that many claim it is.