“It’s like riding a psychotic horse toward a burning stable.”

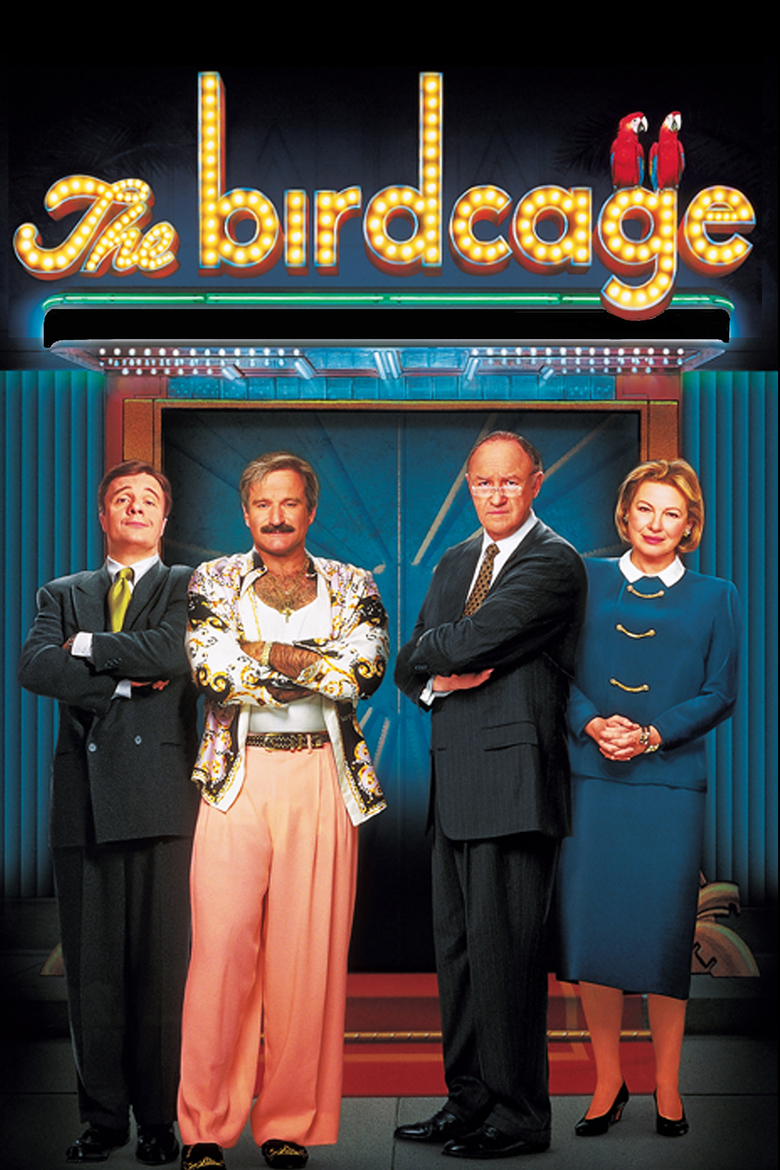

I’m a little bit conflicted on how to approach writing about The Birdcage. On the one hand, I found it to be terrifically funny. It’s based on an excellent script from early Mike Nichols collaborator Elaine May, who adapted an old French film called La Cage aux Folles and added some Americanized deep cuts. There are superbly flamboyant performances from Nathan Lane and Hank Azaria, and one of those in-between Robin Williams roles where he’s goofy but in control of his hysterical outbursts and has a few powerful moments of serious vulnerability. On the other hand, the film is seen in retrospect as a watershed moment in the depiction of homosexuals and transvestites in popular media. That’s all well and good; and while I support people’s right to choose such lifestyles, it seems that in the current social climate refraining from celebrating such orientations or resisting the push to thrust them on young people is seen as equivalent to condemnation. This predicament is further exacerbated by the LGBT+ monolith, which threatens to swallow up all meaningful conversation and drown it in bile before any progress can be made—e.g. if you support the right for a man to sex another man or dress as a lady, you’re automatically also endorsing state-funded elective surgery and hormone blockers for children and pedophilia and people marrying sex dolls. There is very little leeway to exist in between abhorrence and condonement. But that’s where most people actually find themselves, and anyone who can unglue their eyes from 24/7 news media long enough to have a real conversation with them would know that. But at the end of the day I watched The Birdcage because I wanted to see a good movie. And it is a good movie, largely because, in contrast to agenda-laden films of the modern era, its politics are organic and used to entertain and evoke laughter and compassion rather than to browbeat.

The setup of The Birdcage is absurdly farcical. Armand (Williams) is a gay Jewish man who owns a drag club in South Beach. His partner is the cross-dressing Albert (Lane), who goes by Starina when he performs at the kitschy cabaret shows. Albert suffers horribly from insecurity, and the film opens with his refusal to perform because he thinks Armand is seeing another man while he is on stage. With the help of Guatemalan houseboy Agador (Azaria), who offers the effeminate singer “pirin” tablets (“What are you giving him drugs for? What the hell are pirin tablets?” “It’s aspirin with the ‘a’ and the ‘s’ scraped off.”), Armand is able to coax his lover in front of the crowd where he sinks into his element. While he performs, Armand does see another man, the young Val (Dan Futterman). Their encounter is odd and the nature of their relationship remains veiled for a ridiculous amount of time, until it is revealed that Val is Armand’s son, the result of a one night exploration of opposite-sex relations between himself and Katherine (Christine Baranski). Much of the film is built on these weird, tense encounters that relish the awkwardness and use it for situational hijinks.

Val requested a private audience with his father to inform him that he is planning to marry a young woman named Barbara (Calista Flockhart). The catch, and the reason that Val wanted to speak to Armand privately, is that Barbara is the daughter of right-wing Senator Kevin Keeley (Gene Hackman) who will no doubt disapprove of his daughter’s groom if he finds out the young man was raised by a gay couple. At his son’s urging, Armand reluctantly agrees to pose as a straight man while hosting the Keeleys for a dinner party. He even calls up Katherine, who has never met her adult son, and convinces her to join them and complete the illusion of a traditional American family. Initially, the plan is to have Albert pose as an uncle. There is a very humorous scene in which Armand tries to teach Albert how to act masculine but Albert regularly falls out of the act and reverts to his feminine persona. He holds his cup with his pinky extended, he doesn’t understand how to spread mustard like a man, he can’t make small talk about football. The standout moment from this byway is when Armand tries to inform Albert’s stride. “Let me give you an image,” he says. “It’s a cliché, but it’s an image—John Wayne. He’s got a very distinctive walk, very easy to imitate. And if anyone is a man… okay, now try it. Just get off your horse, and head into the saloon.” Albert sidles around the outdoor dining area, greets another patron with a “howdy” and returns to their table. “No good?” he asks. “Actually, it’s perfect,” Armand says. “I just never realized John Wayne walked like that.”

It quickly becomes clear that Albert is simply too flamboyant to pass as a straight man. In fact, adding masculine elements willy nilly only enhances his feminine characteristics. After several failed attempts to masculinize him, Armand, eager to please his son, requests that his partner vacate the premises for the evening. They remove all of the erotic decor in their flat—which means it has the austere look of an ascetic’s sleeping quarters—hang up a crucifix, and prepare to meet the Keeleys. But Armand quickly realizes that Albert’s dismissal puts their relationship in jeopardy, and he tracks him down, leading to a tender moment between the two in which Armand hands his partner palimony papers that list Albert as the co-owner of all of Armand’s property. It’s one of those instances where Williams kind of blows you away with his dramatic ability. There are a few poignant moments like this that are made effective by the actor’s restraint elsewhere.

As the founder of “The Coalition for Moral Order,” Senator Keeley finds himself in the midst of a scandal—his trusted colleague and co-founder of the order has died of a heart attack in the bed of an underage prostitute. The last thing that his family needs is to be discovered traveling to the homosexual hotbed of South Beach, but Val and Barbara cook up some stories on the fly in order to convince Kevin and his wife Louise (Dianne Wiest) that announcing their engagement will be a political balm for the Senator. They tell him that Armand is a cultural attaché to Greece and that Val’s mother is a housewife. Things are set up nicely when, rather than disappear or pose as a member of the family, Albert locks himself in his room, forcing the remaining Goldman’s to pretend that the sobs emanating from the room come from a dog and that Val’s mother will be there shortly.

The dinner scene escalates into comic absurdity. Albert enters dressed and made-up as a middle-aged woman and poses as Mrs. Goldman, giving a splendid performance that echoes Williams’s similar role in Mrs. Doubtfire. Agalor, who is renamed Spartacus for the dinner, clomps around in unfamiliar shoes and a suit. He quickly serves a light stew, the entirety of the meal he has prepared for the night, in order to cover up the explicitly homoerotic images that adorn the bowls. Keeley takes a liking to Mrs. Goldman and her strong conservative values. It’s a grand farce that rises to ridiculous levels until it all comes screeching to a halt when Katherine arrives and is greeted by the Keeleys, forcing Albert to reveal himself. The ending, in which Gene Hackman dances out of the club in drag in order to avoid the paparazzi, feels a little bit light, but it works fine enough.

The juxtaposition of the Keeleys’ conservative values and the hedonistic culture of South Beach serves as the platform for many of the film’s best gags, with comic jabs being thrown in both directions. Keeley is a caricature of his beliefs, but then the whole film is “about” adhering to stereotypes. I feel like the audience for a film like this has probably shrunk in the years since its release, as the political divide has seemingly widened and each side has become reluctant to engage with the art produced across the gap. This film exists in the murky gulf between the current renditions of America’s political systems of thought and those who tread here are often not welcomed by either side. In any case, The Birdcage is hilarious. Relax a bit and enjoy it.