“Man… probably the most mysterious species on our planet. A mystery of unanswered questions. Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? How do we know what we think we know? Why do we believe anything at all?”

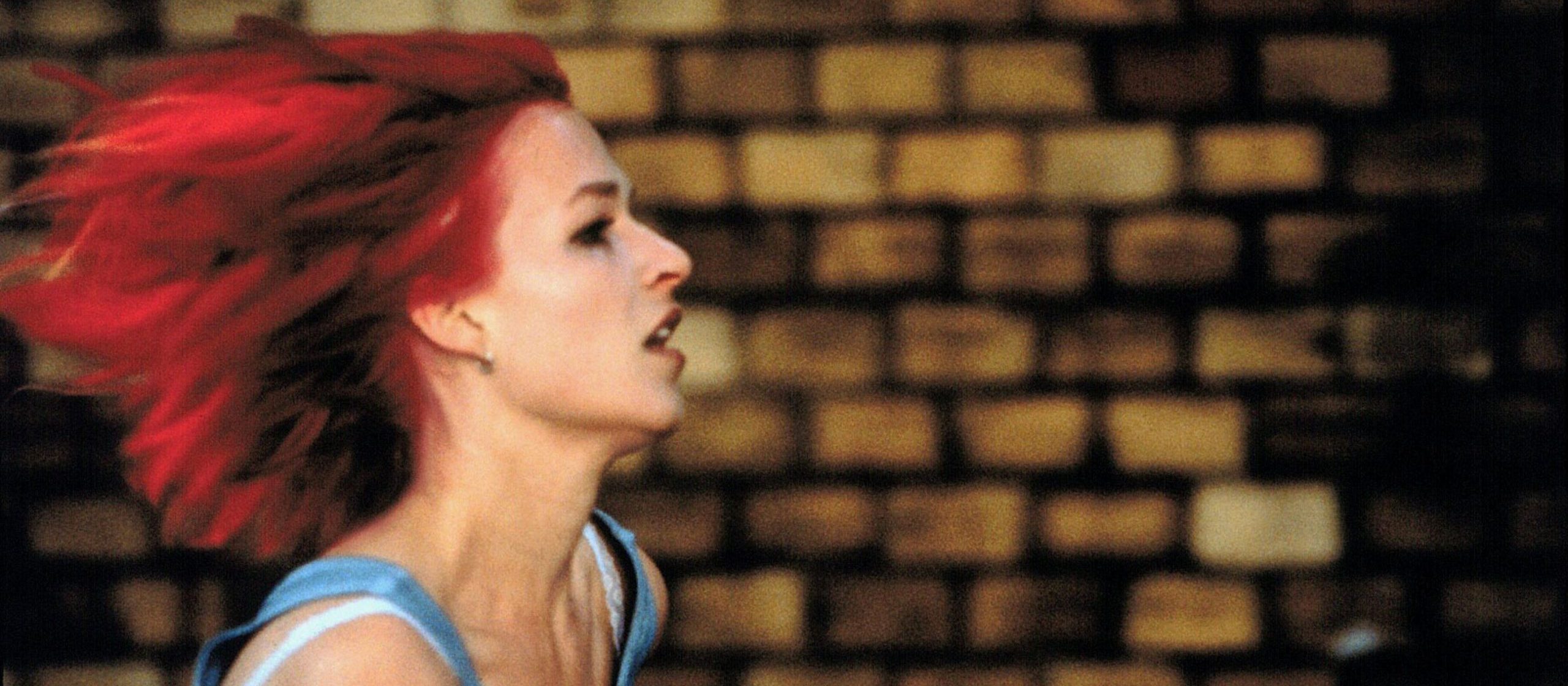

Like the early films of the French New Wave, Tom Twyker’s Run Lola Run is unmistakably marked by an exuberance found in the act of moviemaking. There’s an infectious energy to it, a kinesis achieved through sublime camerawork, innovative editing, and pulsating music, so overpowering that even a cynic will find themselves tapping their foot to the techno beats that fuel the protagonist’s endless sprinting and mask the film’s basic weightlessness. Lola runs, and the camera glides and dances along with her. Footage is slowed down and sped up. The color scheme alternates between vivid primary colors and black-and-white. Several segments blend live footage and animation. Others make use of a split screen. Any time we move away from the main characters, the medium shifts from film to grainy video. Rapid-fire montages are flung onto the screen accompanied by the pop of flashbulbs, running forward and backward in time and parallel to the main story.

The ball is round. The game lasts for 90 minutes. Everything else is just theory.

This invigorating style is used to coax the audience into an ambiguous nonlinear storyline that broaches ideas of free will, chance, and the butterfly effect. The setup involves Lola (Franka Potente) receiving a frantic phone call from her careless boyfriend Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu), a low-level bagman who has botched a courier job and lost a hundred thousand Deutschmarks—a hundred thousand Deutschmarks that he is expected to hand over to his boss in a mere twenty minutes. He believes that he will be killed if he arrives without the money. In his panicked desperation, he tells Lola that he will rob a grocery store if she cannot conjure a solution out of thin air. Lola’s first instinct—selected from a blur of faces that are swiftly thrown up on the screen one after another—is to beg her wealthy father (Herbert Knaup) for the money. She dashes to his office and interrupts a tender moment between him and his hitherto unknown mistress, which sets off a tirade about Lola’s rebellious ways. No dice. With her initial plan foiled she helps Manni rob the grocery store, only to be gunned down in the street by a jumpy cop.

Mentally retracing the million tiny occurrences that led to her death, Lola envisions an alternative path, then travels back in time to when she first received Manni’s call, and tries again. (Is this the first time a film employed video game logic so thoroughly?) This time she makes subtle changes, anticipates, takes shortcuts, and strives to achieve a different outcome. It isn’t until the third attempt that fate smiles upon the outlaw couple and they walk away unscathed and carrying the money.

Though thematically quite shallow, Run Lola Run includes at least one neat trick in its creative bag that I thought brilliantly illustrated its main thesis, which is that every small decision gets rolled up into our lives and remains a factor in our future circumstances. When Lola encounters random characters—often whizzing past them at full tilt—the image rapidly flickers as a series of still photos are presented that depict the future of that character. These various futures change throughout Lola’s alternate scenarios, some ending in ruin, some in fortune. These ideas are explored elsewhere: in the interlude scenes (game over screens?) where Lola and Manni lay next to one another, musing on life and love and fate; in the way her father’s life paths wildly diverge depending on the exact moment she interrupts his conversation.

But it’s never too serious or too deep, and it’s clear that it is the director’s visual prowess and the adrenergic editing style, rather than the pop philosophy or the weak characterizations, that elevates Run Lola Run and prevents it from feeling like a superficial exercise. Indeed, it is best not to get too hung up on the prefatory quote from T.S. Eliot and symbolic references. Instead, luxuriate in the rhythm established between the soundtrack and the action, the colorful blurs of movement, the overwhelming sensation. If you need more than that, it’s there, however plainly, but without the momentum of the visuals and music, the story wouldn’t amount to much.