“I’m old fashioned. I don’t believe in extra-marital relationships. I think people should mate for life, like pigeons or Catholics.”

You’ll often hear Manhattan referred to as a love letter to New York City. I think this is incorrect, or at least misses the actual point. The film opens with a humorous monologue from its writer-director-star, Woody Allen, riffing on the very first sentence of a book that his character wishes to write about his hometown. From his numerous false starts we learn that despite the seedier elements of city life, he is held enraptured by the unending possibilities that exist around every street corner. It is true that the city is bustling with life and potential futures. As his stop-start spiel unfolds, Gordon Willis’ camera lovingly frames all manner of diners, stadiums, art galleries, blacktop basketball courts, apartment complexes, dry cleaners, bridges, theaters, parking garages, street vendors, gondolas, construction crews, ferry boats, and so on, each of them alive with human activity. When our leading man finally settles on a suitable opening to his book, the camera frames a picturesque fireworks display just as ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ swells.

This introduction is certainly romantic in the sense that Isaac Davis (Allen) is clearly in love with his hometown; but it is spoiled by the fact that he is incapable of expressing his feelings in an articulate manner. He discards several rough drafts before settling on a questionable line: “He was as tough and romantic as the city he loved. Behind his black-rimmed glasses was the coiled sexual power of a jungle cat. New York was his town, and it always would be.” And so, when these words are juxtaposed against celebratory fireworks and classical music, we must ask what exactly they’re celebrating. Not the achievement of his book—which is yet to be written and sounds like it will be horrendous—but the feelings that the city evokes within him, the mystique of the “town that existed in black and white and pulsated to the great tunes of George Gershwin.” In other words, his numerous restarts are not attempts to more accurately represent the city, but to more accurately represent the feelings he has for it. The contradiction that arises, then, is that these feelings are barely attached to reality, as evidenced by the fact that he has to start again each time he drifts toward a clear-eyed description.

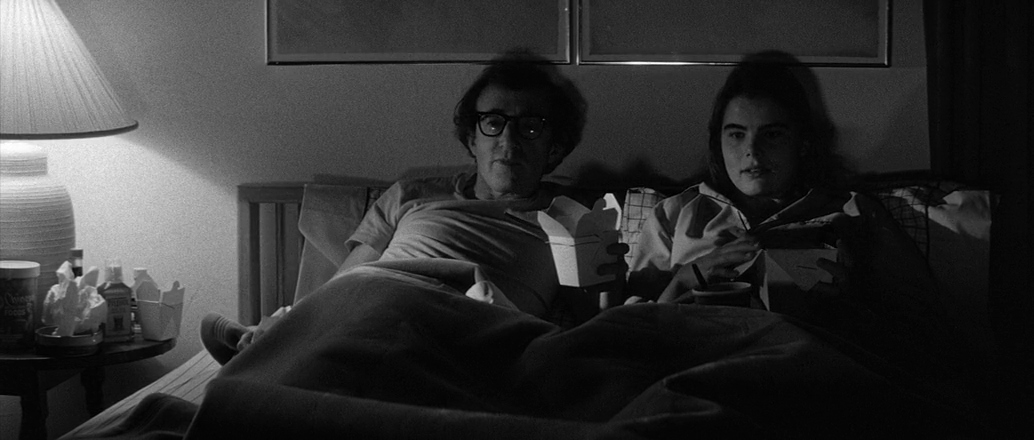

This contradiction holds in Isaac’s personal life as well. A twice-divorced forty-something writer for television, Isaac views his interior life in the same way he views New York City. Just as he stammers his way through several lines of thought and then crosses them out when he unintentionally begins speaking of rampant drug use, garbage in the streets, and the decay of contemporary culture, so too he chooses not to interrogate his own personal shortcomings and lack of integrity. At least, not at first. For instance, even while he criticizes his best friend Yale (Michael Murphy) for having an affair, he engages in a manipulative short-term relationship with seventeen year old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), encouraging the smitten young lady to consider their relationship a mere “detour” in her life. But of course that fact wouldn’t stop him from engaging in casual sex with a minor.

You get the sense that Isaac is trying to conform to a nebulous ideal, and it’s not God as he half-jokes late in the film. The first scene after the montage finds him in a jazz club with Tracy, Yale, and Yale’s wife Emily (Anne Byrne), smoking because, as he says, it makes him look handsome. Later on, when he and Tracy visit an art gallery, his vacuous young girlfriend has nothing to say about a photo exhibit and meekly agrees with his learned opinions. But when they run into Yale and his neurotic mistress, Mary (Diane Keaton), Isaac and Mary butt heads pretentiously decrying the merits of the modern “artworks” that they’ve observed. Mary hates the plexiglass sculpture that Isaac purports to enjoy, while she loves the steel cube that does nothing for him. And so Isaac finds himself reeling, both intimated and smitten by this mysterious woman. In no uncertain terms, she becomes the new ideal woman in his mind, the exciting new possibility that he’s discovered after turning another corner of his beloved city. Eventually, Mary disentangles herself from her affair with Yale, Tracy makes plans to study theater in London, and Isaac and Mary strike up a romantic relationship. But this just starts his cycle of discontent all over again and leads to more self-deception and self-righteousness. There are only a few instances where Isaac’s façade shows cracks. One is when his friends read from his ex-wife’s (Meryl Streep) autobiography, which details his failures; the other is when he returns to Tracy to plead for her not to go to London, but pauses for a moment when he realizes that his desires are entirely self-centered.

It’s a very dense script full of characters whose thoughts ramble all over the place, effectively creating fleshed out individuals who exist beyond the boundaries of the story. One of my favorite discussions, filmed in a long take as Isaac, Tracy, Yale, and Mary walk along the sidewalk, introduces Mary’s idea of the Academy of the Overrated, which includes such figures as Gustav Mahler, Isak Dinesen, Carl Jung, F. Scott Fitzgerland, Lenny Bruce, Norman Mailer, Vincent van Gogh, and Ingmar Bergman. “Bergman is the only genius in cinema today!” Isaac retorts.

But the inherent tension in the film comes from the mismatch between the disenchanting content of the screenplay and the beauty of Willis’ cinematography and Gerschwin’s compositions. Indeed, I think it’s entirely possible to watch the film with an undiscerning eye and get swept up by the visual and aural experience and completely miss the despicable characteristics of Isaac Davis. I think this incongruity is best illustrated by a surreal scene in which Isaac and Mary dodge a rainstorm by entering a planetarium. As they seemingly wander through the cosmos in silhouette, Isaac cleverly manipulates the conversation to orchestrate a poetic moment. And because all of the cinematic clues point us to believe it is a touching moment, we tend to accept it as one.

In this way, Allen manages to romantically depict a decaying city full of protean individuals for whom jobs, values, ideologies, religions, and relationships are just temporary stances that can be embraced or modified or discarded at any time. Ideas and ideals shift according to mood and no one knows at any given time where they might stand, let alone how an acquaintance’s viewpoints or allegiances may have changed. The film is essentially an excoriation of the type of person Isaac represents, which, through image and sound and Allen’s characteristically witty script, tricks people into accepting its deceptions. I think some people pick up on the familiar cinematic cues and comprehend Manhattan as endorsing this shallow, noncommittal romanticism, this “grass is always greener” mentality. I don’t see it that way at all.