“A handsome youth in the morning, once lured by that merciless wind, is by dusk a heap of bones. In the end, all must die. Countless people have sinned on their way towards death. Could the law even begin to punish them all? Some may slip through the law’s net, but they cannot elude their own consciences. Religion dreams of a world where sinners are punished after death for sins unpunished during life. That world is Hell.”

Jigoku (rendered in English as The Sinners of Hell) is a folk-tale inspired horror film directed by Nobuo Nakagawa, a director whose varied career eventually became defined by his work on kaidan—Japanese ghost stories told in an intentionally old-fashioned style. Dissimilar from modern Japanese horror films such as Ju-on or Ringu, which are more intentionally focused on horrific elements, Nakagawa’s haunting films compel through atmosphere and memorable stylistic visuals. Jigoku is a cult classic; its tale of morality and karma draws on Buddhism for its concepts of retribution, afterlife, and atonement for earthly sins. The film’s two halves contrast starkly, with its culminating evocation of Hell arriving only after a mostly forgettable first act.

Jigoku is part noir, part surrealist cinema. The film begins with a stylish opening credit sequence that exemplifies fleshly temptations by subjecting the viewer to a montage of half-nude women. A voiceover delineates the film’s philosophical framework as we are shown images from the film’s climactic scenes. We then cut to the beginning of the main story, as a professor gives his lecture, titled Concepts of Hell. Shirō (Shigeru Amachi) is absorbed in the lecture for two reasons. The first is that he is engaged to be married to the professor’s daughter; the second is that as Professor Yajima (Torahiko Nakamura) describes the Eight Hells through the lens of the Buddhist sutras, Shirō cannot shake the memory of the night before.

We jump back in time. Shirō’s classmate, the devilish Tamura (Yōichi Numata), is chauffeuring Shirō home, when he accidentally hits and kills a drunken Yakuza gang leader. He continues driving, blaming the accident on the drunk man, and convinces Shirō to keep his knowledge of the event to himself. The accident is also witnessed by the gangster’s mother, who plots to enact revenge on the two men.

Shirō confesses the crime to his fiancée, Yukiko (Utako Mitsuya), but as they take a cab to the police station to confess the crime, Yukiko is also killed in a car accident. In the scene, Shirō imagines that the taxi driver briefly morphs into Tamura. Seeking solace from his grief, he spends the night with a prostitute, Yoko (Akiko Ono), who is coincidentally the lover of the dead Yakuza gang member.

Throughout the rest of the first act of the film, the people around Shirō gradually meet their demise. Shirō travels to visit his sick mother, who is staying in a retirement community run by his father, and finds her amidst her own collection of shady characters. Among the town’s inhabitants are Ensai (Jun Ōtomo), a disgraced, alcoholic artist commissioned to paint a depiction of Hell; and his daughter Sachiko (also Utako Mitsuya), a dead ringer of Shirō’s departed fiancée who takes care of his dying mother. Shirō’s father has fallen into moral depravity, and has taken a young woman as a lover while his wife slowly dies.

Yoko tracks Shirō to the retirement community and confronts him on a rope bridge. Revealing herself, she tries to shoot Shirō, but in her haste she slips and falls from the bridge to her death. Tamura reappears, and at a drunken party he begins to call out the moral failings of the townspeople, claiming that they are all complicit in the deaths of others. Shirō’s father was unfaithful to his mother; the doctor did not object to a misdiagnosis; the detective framed someone; the journalist was guilty of slander; and Yukiko’s father stole his comrade’s last sip of water in the war. In rapid succession, the characters parish in a variety of ways—suicide by train; food poisoning; gunshot; strangulation; hanging.

The first act of the film is serviceable, but very conventional. Nothing truly noteworthy, but it is not entirely without merit. It simply wouldn’t be known today if the whole film remained in that vein. But, when the second act of the film begins, we see the reason that Jigoku is considered a cult classic and still watched today. We are in Hell; or, at least some kind of Buddhist limboid netherworld.

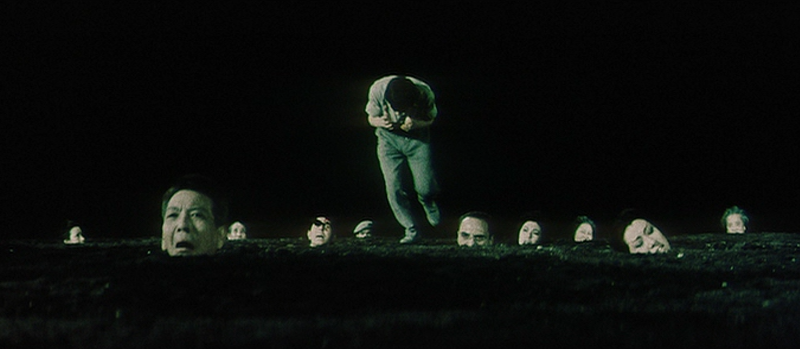

The latter portion of the film is a visual spectacle, and one that holds up incredibly well for its era. The filmmakers utilize water vapor, colored lights, and creative imagination to evoke something akin to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Shirō finds himself at the River Sanzu, a kind of boundary between life and death, and from here his variably grotesque and poetic journey through the abyss begins.

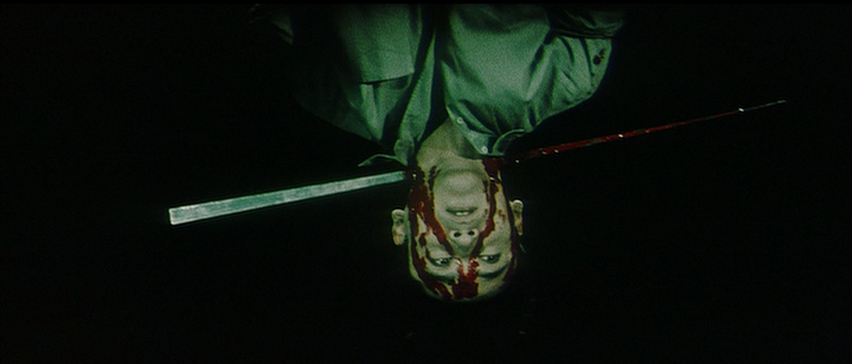

Suspended upside down and with the blade of a sword through his neck, Shirō is condemned by Lord Enma to punishment in the Eight Realms of Hell. The scene blurs into an encounter with Yukiko, who informs Shirō that she was pregnant when she died, and the cry of their child lures him further into Hell.

As he searches for his daughter, Shirō sees his acquaintances suffering in various ways for their sins. Many of these scenes are gruesome, and earned Jigoku the reputation of being the first “splatter” film. People are boiled alive, dismembered, and beaten by ogres. Tamura appears to taunt Shirō, but he is soon slaughtered for submitting his life to evil. Shirō finds Sachiko in a place where glass shards protrude from the floor, but Shirō’s mother interrupts to inform her son of her own infidelity, and confess that Sachiko is actually Shirō’s sister.

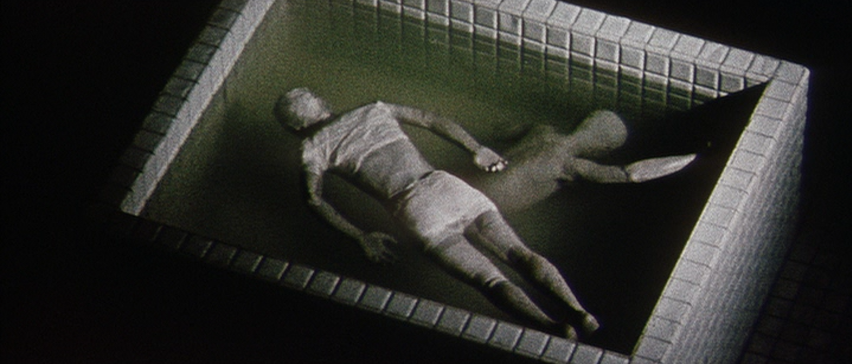

Lord Enma gives Shirō a single chance to save his child as she spins helplessly on the Buddhist Wheel of Life. As he jumps onto the wheel, it freezes in time, and we cut to the disgraced painter Ensai hanging by the neck above his completed painting of Hell. In the coda, Sachiko and Yukiko—Shirō’s sister and lover, respectively—stand in a hazy light, smiling and calling to him as petals from lotus flowers fall to the ground.

Jigoku would have been amazing to see in a theater when it was released. This was well before film’s like Bonnie and Clyde or The Wild Bunch, even though its arthouse tendencies make its target audience different from that of Hollywood. The dated effects are certainly not realistic, but the content is undeniably shocking—beheadings, flayings, dismemberment, etc. At least in Psycho the blood is muted by the black-and-white color scheme, but Jigoku is in color, a stylistic choice which is utilized to great effect. The color is used effectively to expand the inner world of the protagonist and to enhance the visual spectacle of the underworld.

A stylistic descendent of Benjamin Christensen’s silent classic Häxan, Nobuo Nakagawa’s film was simply ahead of its time—in almost all cases, it pushes the envelope beyond its contemporaries; and the responses to those coeval attempts at horror were mostly shock and dismay. Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom were both met with with such criticism; among horror films from fellow countryman, Onibaba occupies a unique place among the genres of horror, social critique, and period drama, while the most apt comparison—the phantasmagoric and visually stunning Kwaidan—was not released until five years later. The imagery portrayed is akin to the works of 15th century Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch (whose work is featured prominently in Martin McDonagh’s black comedy In Bruges—it is fascinating how art is endlessly inspirational).

Although Jigoku is not compelling throughout its entire runtime, its visually innovative and memorable climax is worth a viewing for students of film history and those intrigued by depictions of the underworld.