“What was I supposed to do? Call him for cheating better than me in front of the others?”

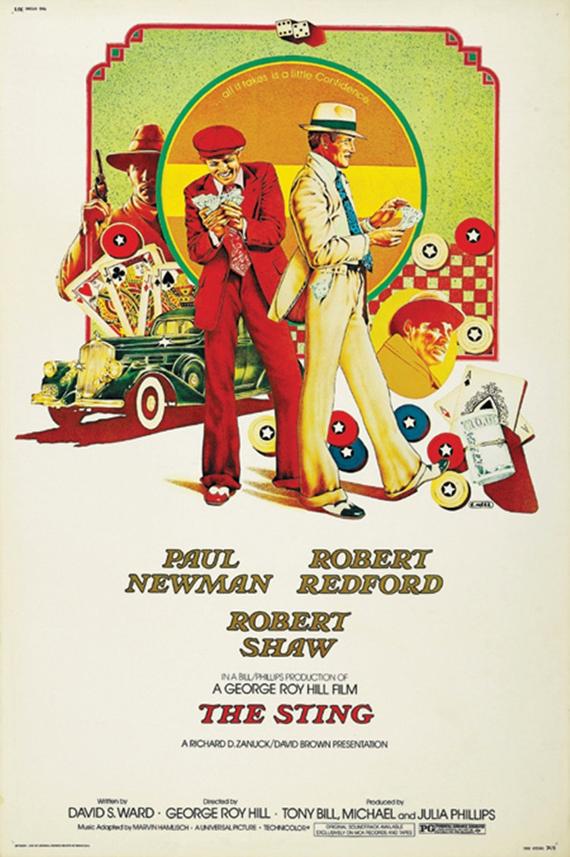

After the successful pairing of Robert Redford and Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), director George Roy Hill got the charismatic duo back together several years later for The Sting, a rollicking story of conmen and mobsters that is oozing style, hits all the right beats, and avoids taking itself too seriously. Like Butch Cassidy, The Sting is slightly playful, featuring a comedic and lighthearted tone throughout as it details the “long con” of a vicious mob boss.

Johnny Hooker (Redford) is a small time grifter who is content on conning a few bucks here and there to make ends meet and blow the rest on gambling. When he and his pals unknowingly rip off a courier of crime boss Doyle Lonnegan (Robert Shaw), Lonnegan puts out a hit on them that leads to the death of Johnny’s mentor. Before his untimely demise, Luther (Robert Earl Jones1) had announced his retirement from the con game, recommending that Johnny look up his old friend Henry Gondorff (Paul Newman) to teach him the “long con.” Given the impression that Gondorff—who goes by the alias of Shaw—would be a consummate professional, Hooker is thrown off guard by the hungover scammer who he finds hiding out from the FBI. He finds Shaw fallen off of his bed, his face pressed against the wall, snoring. It isn’t until he chunks a block of ice in the sink, fills it with water, and dunks his head that he Shaw takes on the air of a professional, finally committing to rounding up a team to con Lonnegan as revenge for Luther.

On the surface, The Sting appears to play out methodically, with its title cards and behind-the-scenes look at the methods used for fooling the mark. First is the set-up—Shaw gets himself invited to a high-stakes poker game aboard a train, and out-cheats the cheater at his own game to the tune of $15k. His choice of tactic—to get a little bit drunk and appear careless with his gambling—along with the general scenario reminded me of James Bond in Fleming’s Moonraker. By posing as a disgruntled employee of Shaw’s, Hooker convinces Lonnegan to help him cheat his boss, who “owns” an off-track betting parlor for horse races. In reality, the entire betting operation is composed of con men brought in to sting Lonnegan. The cast of supporting roles are uniformly excellent, from the ticker-tape reading Ray Walston, to Harold Gould as a fake Western Union rep, to Tom Spratley auditioning for a role in the con by saying, “Me specialty’s an Englishman.”

In addition to its stylish and exciting romp towards Lonnegan’s fortunes, the film is also working the viewer, leading up to a brilliant twist that will catch you off guard even if you’re looking for it. A subplot involving a corrupt police chief aiming for Hooker keeps things from feeling too easy, and another regards a faceless pair of black-gloved hands whose owner is constantly surveilling him. The film never gets too hung up on details of the details of its elaborate game, and the strong screenplay leaves enough ambiguity about who is doing the double crossing to leave the audience in suspension until the closing moments of the film.

Set in the final years of the Great Depression, The Sting looks and feels much older than it is. Hill made conscious choices to give the film its vintage quality, such as utilizing iris shots and wipe transitions, and opening the film with the old Universal logo. The ragtime tunes of Scott Joplin were adapted for the film as well (although they were actually popular several decades prior to the era in which the film is set). The story is partitioned by illustrated title cards denoting the stages of the con, and the detailed set looks great.

Just as they were in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Redford and Newman are underdogs and outlaws in The Sting. But where in the earlier film their camaraderie was the selling point, and the film was much more belabored, finely tuned, and concerned with creating serious art, in The Sting their performances are more geared toward propelling the thrilling story. It’s shot plainly and lets the screenplay and performances do the heavy lifting. As a result, The Sting feels loose, free, and fun. Its large cast and myriad voices at times resemble the ensemble films of Robert Altman (McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville), but the two leading men are clearly the stars. Robert Shaw (best remembered now for this film, along with his roles in From Russia with Love (1963) and Jaws (1975)) gives a subtly brilliant performance as Lonnegan, imparting his character with enough menace and cold-hearted viciousness that his threats are taken seriously, but also with a hint of vulnerability and pride that allows his slip-ups to be believable.

The Sting features high production value, two stud actors, and doesn’t make any obvious blunders; it has pretty much everything going for it. My minor criticisms of the film are that shooting the bulk of it on studio lots resulted in a vague feeling of claustrophobia especially considering its sprawling cast and action sequences, and the plot contrivances that shift the audience sympathies to one set of criminals instead of the other. In the first scene of the film, Luther and Johnny indiscriminately steal from a man who just so happens to be a criminal, retrospectively coloring our perceptions of the con. If they had casually stolen from a man whose wife was dying of cancer, it would have derailed the whole thing; yet they presented the target as random.

Though The Sting wasn’t the first con movie—there are plenty of classic caper films like Rififi (1955), Bob le flambeur (1956), and The Killing (1956)—it is probably the oldest one that remains relevant to mainstream audiences. It is a touchstone that has served as inspiration for a plethora of modern con and heist films, including The Usual Suspects (1995), Catch Me If You Can (2002), and the Ocean’s trilogy; though perhaps no film is quite clearly as inspired by it as Mamet’s House of Games (1987). The Sting is about as classy and fun as one can expect a popcorn flick to be.

1. Father of James Earl Jones, most famous as the voice of Darth Vader in Star Wars and its sequels.