“A little venom in your blood is a good thing.”

For viewers of a Christian persuasion, one way to tackle Ridley Scott’s biblical epic, Exodus: Gods and Kings, would be to dismiss it outright; to point out the myriad instances where the agnostic director deviates from a source that they consider sacred and infallible—the very Word of God. Such an approach would immediately generate a laundry list of offenses, chief among them God the Father’s appearance as a young British boy and Scott’s insistence on presenting the many miraculous events depicted as naturally caused. There are many other embellishments, exclusions, and misplaced emphases. Moses wields a sword but not a staff; Moses is extremely talkative while Aaron is a non-factor; Moses’ staff does not transform into a snake. And so on and so forth. But to get to the point of earnestly critiquing Scott’s film for its brazen disregard of the text of scripture, one must first subject themselves to two and a half hours of mind-numbing CGI spectacle and soulless drama that is, quite frankly, a sprawling mess. So even if one wishes to have a conversation about Scott’s skeptical take on the material, the variety of possible interpretations of the passages, whether the film can appeal to both Christians and secularists, etc. the fact that the film lacks an engaging script and is almost entirely shot against a digital backdrop basically precludes taking it seriously as a work of art, let alone a thoughtful treatment of the the book of Exodus.

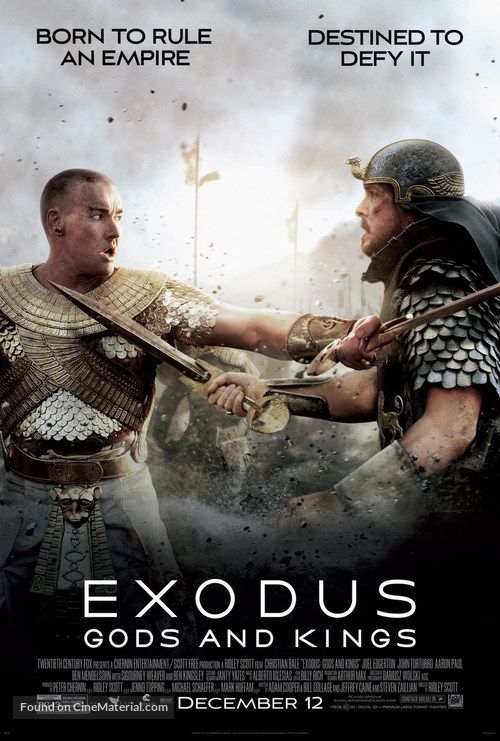

The story of Moses (Christian Bale) rising up against the Pharaoh Ramesses (Joel Edgerton) is one that many people are familiar with as various religions draw on the Old Testament texts as authoritative. There’s the burning bush, the plagues, the Ten Commandments, the parting of the Red Sea. It’s the reason that Jews celebrate Passover, which was reconstituted by Jesus in the Christian sacrament of Communion. In Scott’s retelling, from a script credited to four writers (Adam Cooper, Bill Collage, Jeffrey Caine, Steven Zaillian), several elements are left out, like Moses’ trip down the Nile in infancy and the Israelites’ worship of the golden calf. But he doesn’t reinvent the wheel. By and large he’s simply retelling the story from a skeptical point of view by cutting out the narrative’s connective tissue and presenting its highlights.

The film begins as Moses and Ramesses prepare to ride into battle against the Hittites. A high priestess divines a prophecy from the intestines of a sacrificed bird that indicates one of the leaders will fall in battle and that his savior will one day lead. In the ensuing skirmish, Moses saves Ramesses from certain death, casting a dark shadow over their brotherly relationship going forward. When Ramesses’ father Seti (John Turturo) dies and Ramesses becomes the new Pharaoh, Moses becomes his advisor, but he’s soon chased out of the royal court when it is revealed that he is a Hebrew.

In exile, he gets married, has a child, and becomes a shepherd. It is while tending his sheep in the wilderness that he encounters Yahweh and Scott presents his first major deviation. God appears in a burning bush (or at least near one), but this only occurs after Moses has been caught in a rock slide and rendered delirious. Is God’s bodily appearance to Moses merely a hallucination? And likewise, when Moses demands that his estranged stepbrother free the Hebrew slaves and Ramesses’ refusal prompts a series of plagues, is it possible that these are all naturally caused? That’s what’s posited here. A frenzy of crocodiles gobble up some unfortunate souls in the Nile, filling it with blood. The blood prompts innumerable frogs to get out of the river and find new lodgings in Egyptian bedrooms. The frogs die without adequate water and attract flies. The flies cause nasty boils. Etc. When the last plague comes—the death of every firstborn whose family did not paint their doors with the lambs’ blood—no natural explanation is offered. But then we’re back to naturalism when a distant meteorite hits the water and causes the sea to part to allow the fleeing Hebrews to escape the pursuing Egyptian army.

But like I said, it doesn’t even really matter that Scott and his gaggle of screenwriters want to play fast and loose with the text of the Bible because the film is unengaging on a more basic level. Indeed, the lack of reverence for the material might be the least of the blunders here. The costumes, props, and small-scale sets appear tasteful and adequate in the early going. Even the computer generated overview of Egypt looks decent. But as soon as the battles and plagues start, the computer wizards just go to town multiplying the frogs and soldiers, creating large scale skirmishes and gruesome plagues that should be exciting but are instead bland and boring. The boils, achieved by practical means, are the only effect that doesn’t feel off.

I remain ambivalent toward the issue of white washing. In my opinion, directors should cast whoever they want and let the performances speak for themselves. Scott defended his casting choices by stating that the film would not have been made without them. He’s probably right (surely he needed someone of Bale’s caliber and prominence as a lead), and while I’ll defend his right to do so, I also defend my right to critique those decisions when they don’t work out. In Exodus: Gods and Kings, he has the likes of Sigourney Weaver, Ben Mendelsohn, Aaron Paul, and Ben Kingsley turning in extended cameos. When making a casting decision (or any decision) there’s going to be tradeoffs, pros and cons. Cast Sigourney Weaver as Seti’s wife Tuya and you’ve got a marquee name, a talented actress, etc. But you also have a person whose ethnic profile does not align with the character she is playing. It takes a strong performance for audiences to overlook that ethnic mismatch but it has worked before. And yet, the performances of Weaver, Paul, et al. are a crapshoot of questionable makeup and weird accents. On net, they’re just frivolous distractions, their names exploited for box office draw. Maybe that means their roles should have gone to ethnically correct actors. Maybe it just means that Scott made a terrible movie.

Whether it is the skeptical approach that renders the script narratively inert, or the abundance of copy-paste digital effects that result in bland depictions of battles and plagues, or the uncomfortable presence of various white actors drenched in bronzer and dabbed with eyeliner that precludes emotional connection, Exodus: Gods and Kings is just dead in the water as a cinematic experience.