“Jokes? What jokes? I don’t know any jokes. Look, I don’t even know my own name.”

John Cassavetes is considered one of the pioneers of independent cinema. He acted in countless films and television shows that have long been forgotten, but starred in several notable films, including The Killers (1964), The Dirty Dozen (1967), and Rosemary’s Baby (1968). In the mid 1950s, with only acting credits under his belt, Cassavetes was running an acting workshop in New York City. Using his own earnings along with a minuscule amount of crowdfunding, Cassavetes set to work on Shadows with a budget of $40,0001. For this debut directorial effort, he cast students from his acting classes, and allowed them to “improvise” their scenes (though it is probably more correct to say that they were given the freedom to interpret the script in their own way). In an era when films were backed by studios, the crew broke all the rules and conventions by shooting without permits, using handheld cameras, and editing scenes elliptically.

The resulting film—regarding race relations during the Beat Generation—anchors around a pivotal scene in which a wolfish seducer becomes unsettled when he discovers that the woman he has been seeing is, in spite of her light skin tone, black. The scene occurs halfway through the film, but latent elements present in the film’s earlier portions surface in its wake. Early on, the audience learns that Lelia (Lelia Goldoni) and Bennie (Ben Carruthers) are Hugh’s (Hugh Hurd) younger siblings, despite the contrast between Hugh’s darker skin tone and the lighter shade of the other two. Though Lelia is the central character (and deservedly so, Goldoni dominates most of the scenes she is in), each of the siblings experiences subliminal racism throughout the film. Hugh acts as the family’s guardian and provider, and appears to be level-headed and emotionally stable. His only problems appear to be in his career. Managed by an energetic businessman named Rupert (Rupert Crosse), Hugh is set to perform in Philadelphia, where he is asked to take fourth billing and introduce a group of talentless and provocatively clad dancers. His performance is cut short, though, when the audience appears uninterested in his soulful crooning, yet cheer when the dancers are brought out.

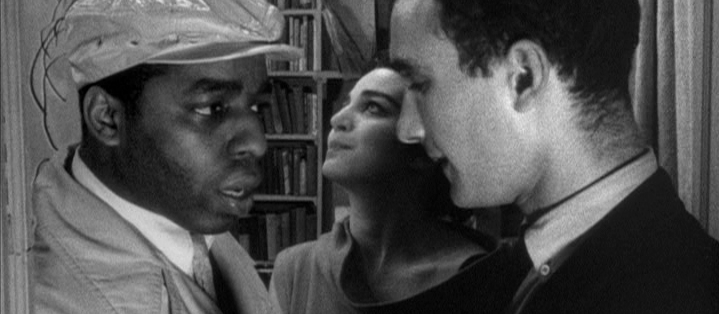

Lelia is the dominant center of Shadows, as she flits about between different love interests. First is an older intellectual who lambasts her literary attempts despite his own instigation being the source of her ambitions. But she is quickly taken by a younger man named Tony (Anthony Ray) who introduces himself at a party. It is only after they have slept together and she has reluctantly allowed him into her apartment (using her apprehension as appropriate foreshadowing for the confrontation) that the revelation happens. Hugh enters the apartment and Lelia introduces him to Tony, who immediately becomes distraught and asks to be excused to go to an appointment that he had forgotten about.

Due to poor reception at initial screenings of the film, Cassavetes reassembled the cast and small crew and reshot much of the footage, recutting the film to emphasize Lelia’s character at the expense of Bennie’s and Hugh’s stories.2 In the first cut of the film, the revelation of her race does not occur until much later, and her interactions with Tony fall well short of the loss of her virginity portrayed in the final cut.3 The most sorrowful episode of the film occurs when Lelia moves on from Tony to a third man, an agreeable African American who is treated harshly by her brothers as well as Lelia herself.

Bennie bookends the film with scenes of alienation and self-effacement. As the opening credits roll and a rocking soundtrack plays, Bennie skulks into the party, hiding himself behind sunglasses and a popped collar. Throughout the film, he appears conflicted between his desire to belong and his wish to avoid attracting attention to himself. Bennie’s angst builds throughout as his relationship with Hugh sours and Lelia confides her troubles in Hugh but not him. When Hugh throws a party in their apartment, the pressure on Bennie causes him to burst and he strikes a woman who had been cajoling him into joining the party. He takes to the streets, then, picking a fight and allowing himself to be beaten before slipping into the shadows.

The film’s impact may not be apparent out of context, so it is important to note the dearth of topically similar films during the era in which it was released. Though some directors used race as an element in their films—such as fellow boundary-pusher Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963)4—the stark treatment of the reality of racism had not yet made its way into popular Hollywood films. Though he was already acting around that time in historically important films like The Defiant Ones (1958) and A Raisin in the Sun (1961), it wouldn’t be until 1967 that Sydney Poitier would star in the seminal race-relations film, In the Heat of the Night. Thankfully, although Shadows faces the issue head on, it doesn’t come off as didactic or chastising. It is very impressionistic and leaves the complex matters unresolved.

In addition to its commentary on race, the film is just as notable for its independent creation and breaking of conventional structure. Cassavetes took the improvised footage and cut it up into a collage of conversations, jumping and and out whenever it pleased him. Many cite Cassavetes as an influence, including auteurs Jim Jarmusch and Martin Scorsese5. His pioneering ways spearheaded a film movement that is alive and well today, with movies being shot on iPhones and published online, entirely removed from the studio system. While its racial commentary and groundbreaking filmmaking methods may not stand out as they did upon release, what remains is still a daring and engaging film. It’s not his best film, but probably his most important one.

1. For some context, the budgets for Some Like it Hot (1959) and Dial M for Murder (1954) were $2.9M and $1.4M, respectively.

2. The original had been lost for decades but was found in an attic in the mid-2000s; a junk dealer had bought it thinking it was an adult film and it had been collecting dust since then.

3. It should be noted that Goldoni is actually white, which seems like an odd casting decision; but given the tight constraints in making the film outside of the system and casting only students from his acting classes, the decision does not seem that disagreeable. She nails the part, so I can’t complain. Unfortunately, she didn’t go on to have a very remarkable career; her most notable credits are supporting roles in Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978).

4. Fuller’s White Dog (1982) is another of his racially tinged experiments, about a dog that has been trained to attack black people.

5. Also, strangely, Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990) seems to have taken a good deal of narrative influence from Shadows.

Sources:

Brek, Madison. “How John Cassavetes Pioneered Independent Filmmaking”. Film School Rejects. 17 May 2018.

Guerrasio, Jason. “Shadowing Shadows“. Filmmaker Magazine. 2004.