“As the sound of the playgrounds faded, the despair set in. Very odd, what happens in a world without children’s voices.”

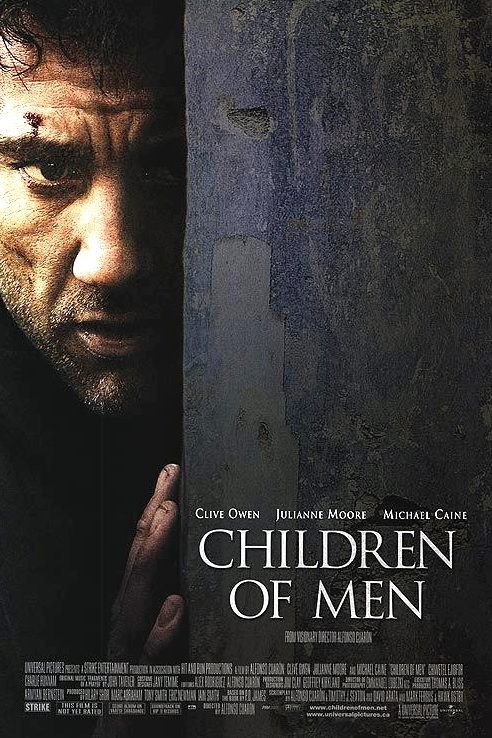

Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men is one of the few truly masterful science-fiction films. It features an interesting concept—humans suddenly become incapable of having children—as well as a fleshed out and detailed future society, stellar acting, and absolutely outstanding camerawork. The protagonist is former activist Theo Faron (Clive Owen), but the story is centered around a young refugee woman named Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey). Kee is pregnant but keeping the fact a secret from the government, as well as from various political and social organizations who would wish to use the baby as a tool.

Based on the novel The Children of Men by P.D. James, the dystopian future is bleak. The government rounds up, cages, and executes illegal immigrants who flee to England, one of the only countries left with a functioning political system. Various religious sects have formed. A militant activist group known as the Fishes is led by Julian (Julianne Moore), Theo’s estranged wife whom he separated from after the death of their son during a flu pandemic. The setting is a fully realized dystopia in the vein of Blade Runner (1982), Minority Report (2002), or Brazil (1985).

Set in the year 2027, we begin our journey in a coffee shop as Theo watches the news. “Baby Diego,” the youngest person alive, has been stabbed to death at the age of eighteen, after he refused to sign an autograph. A bomb planted by the Fishes destroys the coffee shop moments after Theo walks out the door. Ears still ringing from the explosion (terrific sound design), Theo is kidnapped and taken to meet with Julian in secret. They offer Theo a generous sum of money to sweet talk his cousin—a government official—into getting transit papers for Kee so that she can be delivered to the Human Project, a scientific organization dedicated to curing infertility.

The scene in which Theo convinces his cousin Nigel (Danny Huston) to do him the favor illustrates the level of intricate detail of the future world developed for the film. Nigel is in charge of the “Ark of the Arts”, a government initiative to salvage creative works before they are destroyed. When he greets Theo, he stands in front of Michaelangelo’s David with a portion of its leg replaced by a piece of steel, and mentions that a mob had destroyed the Pietà before he had a chance to rescue it. They eat a meal at a large table next to which hangs Picasso’s Guernica, while Nigel’s son ignores both of them in favor of a futuristic computer device that allows him to manipulate the interface without physically touching it. None of these things further the plot, but they add so much flavor and backstory in such little screen time.

Theo is pulled into the Fishes plans when he is only able to secure joint transit papers for himself and Kee, and so finds himself traveling on a secluded road in a car with Julian, Kee, Luke (Chiwetel Ejiofor), and Miriam (Pam Ferris). In one of the most breathtaking and innovative long takes in film,1 the activists are ambushed by several dozen people. Many are on foot, beating on the car and throwing molotovs, but there are two on a motorcycle who shoot and kill Julian. Luke continues driving, in reverse now, and they escape the pursuers. They pass a police cruiser as they flee the scene, and are forced to pull over. Luke quickly executes two police officers, and tells Theo to get back in the car. Only when they drive away from the altercation do we cut from the long take.2

Shortly after arriving at the Fishes compound, Theo discovers that the hit on Julian was planned so that the Fishes could keep the baby and use it as a figurehead for their political activism, rather than deliver Kee and her child to the Human Project. Before her death, Julian had told Kee that she could trust Theo, and so she and Miriam (a former midwife) flee from the compound with him.

They find brief sanctuary with Jasper (Michael Caine), Theo’s drug dealer, who lives in a cabin hidden in the woods. The entire character of Jasper is a delight, and it is fun to see Michael Caine playing a character so different from his usual roles. The long-haired hippie fills in a lot of details about Theo’s former life as an activist, how he and Julian met, and how their son died. He is also the brains behind their new plan to sneak into a refugee camp in order to meet a boat belonging to the Human Project that will pass nearby.

Every time I see Children of Men, I can’t help but smile at Peter Mullan’s portrayal of Syd, a refugee camp guard (and middleman for Jasper to sell drugs to the refugees) who smuggles Theo, Kee, and Miriam into the camp. He brings just the right amount of humor; not enough to pull us out of the drama, but enough that his air of detachment contrasts wonderfully with the non-stop running for their lives that Theo and Kee (and the audience) are enduring. As they are on their way to the camp, Kee begins having contractions, suppressing cries of pain. Syd tells her that she’s not allowed to throw up, but he does not realize the reason for her cries. When he drops them off, he gives them a brief pep talk before forcing them to join the other refugees. “All right. You’re fugees now. Show Syd the fugee face. Sad face. Sad fugee face.”

The climax involves the Fishes trying to recapture Kee and her child—which Theo delivers inside the refugee camp—amidst gunshots and tankfire, in another fascinating long take reminiscent of Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. At one point, blood splatters onto the camera lens and remains for several minutes, constantly reminding the audience that the shot hasn’t ended yet. There is a brief ceasefire as soldiers stop and stare in awe when they realize that Kee is carrying a baby.

From almost any angle, Children of Men is an undeniable success. It will be remembered for its innovative camerawork from cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki3, but the achievement is more than the impressive long takes. The free-flowing story—where plans change, events take the characters off guard, and the situation is evolving moment by moment—is captured perfectly by the raw, documentary-style camerawork. That the shots linger unbroken for minutes on end is a splendid bonus.

I haven’t read the book by James, but I would be shocked if this isn’t the rare case where the film elevates beyond the source material.

1. The shot is nearly equaled by several other impressive shots throughout the Children of Men. There are separate unbroken sequences of three minutes, four minutes, and six minutes. Cuarón had played around with long takes on Y Tu Mamá También (2001), but nothing that required the precise direction of these action sequences.

2. These magnificent shots were not actually single shots. Instead, they were stitched together from several shorter segments. Still, the processes and planning required to capture them (especially the ambush scene) are mind blowing in their complexity. A vehicle had to be created that had movable seats so that the camera could maneuver around the vehicle; the windshield had to be able to tilt to move in and out of the car; and a crew of four had to ride on the roof of the car in order to capture the scene. I should also mention that the transitions are nearly impossible to spot; you can guess when they likely occur, but they are nearly seamless. This is not like Hitchock’s Rope where someone just steps in front of the camera to allow the take to end (keep in mind Hitchcock was limited by the length of a film roll when he tried the gimmick).

3. Lubezki handled the camerawork for many of Cuarón’s films, as well as a handful of Terrence Malick films (including The New World and The Tree of Life). He would experiment even further with the seamless long take in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman.

Sources:

Seymour, Mike. “Children of Men — Hard Core Seamless vfx”. fxguide. 4 January 2007.